If you’d only just met Frank Bruno, you’d never guess the darkness he has walked through.

There was a detached retina, the brutal battles in the ring, and the pressure of being Britain’s favourite heavyweight hero – none of that came close to breaking him.

The real fight came long after the gloves were hung up: being sectioned against his will, and the trauma he says he endured locked behind psychiatric doors.

On the day we meet, in a studio near London Bridge, I hear him before I see him. That unmistakable booming, and genuinely joyous laugh rolls down the corridor. He greets every cameraman like family. ‘What’s up boss man,’ he says repeatedly, like he’s known them for years.

Then, he heads straight to the kettle, spoons two sugars into his tea, and eyes up the birthday cake waiting for him. Bruno turns 64 on Sunday, yet he moves with the swagger and confidence of a man half his age. His broad, expressive face has hardly changed since his fighting days, and despite his massive hands, his handshake is gentle.

We are in a warehouse studio tucked away in a narrow courtyard filming a new show, ClubHouse Boxing. The producers were unsure which type of birthday cake Bruno would prefer, so there are two: one chocolate and one red velvet. The chocolate vanishes first.

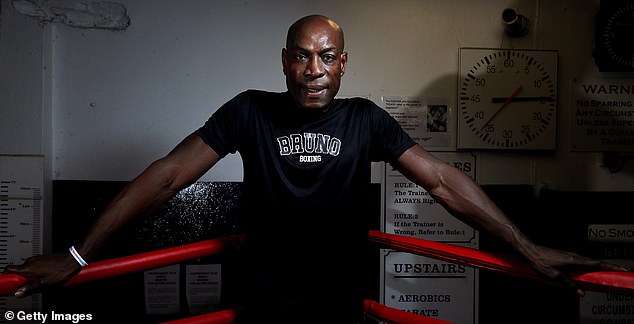

Bruno this week in a studio near London Bridge. He turns 64 on Sunday yet still moves with swagger of a man half his age

If you’d only just met Bruno, you’d never guess the darkness he has walked through yet he still has that unmistakable booming laugh

Ahead of what would become one of his most raw, unfiltered interviews Bruno is pure story-teller.

He laughs as he remembers being eight years old and stealing a barrel of beer, passing out and being so ill afterwards that he says he’s been put off alcohol ever since. He recalls unknowingly ending up at a party hosted by a Colombian drug cartel when he’d travelled to South America for eye surgery at 19.

And of how, as a child, his brother once scrawled ‘Frank Bruno will be world champion’ across their mum’s kitchen wall. His mother was furious – but the prediction came true.

Then the tone shifts.

Bruno begins to speak about September 2003, the darkest chapter of his personal life. He had retired from the sport that had defined him, his marriage had broken down, his children had moved out, and his beloved trainer George Francis had taken his own life. His behaviour had become erratic, his family were frightened and, eventually, they made the decision to have him sectioned.

As he remembers that fateful night, his voice drops. His shoulders lift slightly, as though bracing. The hands that had once thrown punches capable of stopping men cold now fidget in his lap.

‘It was the worst day of my life,’ he says, voice low as he fiddles with a £20,000 Rolex Submariner – a gift from Saudi Arabian sports minister Turki Alalshikh when Bruno was a guest at Tyson Fury’s clash with Francis Ngannou in Riyadh in October 2023.

‘It was a very heavy day for me. The ambulance turned up on the driveway with the police cars behind it. There were reporters climbing over the fences to get pictures. Helicopters overhead filming everything. It was very, very embarrassing.’

‘It was a very heavy day for me,’ Bruno says of being sectioned. ‘The ambulance turned up on the driveway with the police cars behind it. It was very, very embarrassing’

‘It was like living in hell,’ he says of his time in an Essex hospital

He was taken under the Mental Health Act to Goodmayes Hospital in Ilford, Essex. He says he had no idea what awaited him and remembers it as being worse than anything he could have imagined.

‘It’s a weird and a horrible place,’ he claims. ‘I didn’t like it at all, man. They treated me very, very, very rough. They would go out of their way to try and wind you up or distress you. If you’re in a play group or walking around, they would trigger you. Also, if I was messing around with a football, they would come and take the football away just to make you even more miserable.’

Daily Mail Sport reached out to Goodmayes Hospital, who replied: ‘We’re sorry to hear that this was Mr Bruno’s experience of our services. Since his last contact with services at Goodmayes, we have made several improvements to our inpatient environments, therapeutic work with our patients, and a significant investment in recruitment.’

Bruno continues: ‘It was mentally horrible. They treated me like a slave. They’re all corrupted and get kicks out of mistreating the patients. They should all be sacked. Thinking back to it now reminds me of how crazy it was. They should honestly all be sacked and I’m not just saying that. They are horrible people.’

His room, he claims, was no bigger than a prison cell. A bed. A blank wall. No TV. On good days, he was allowed an iPod to try to calm him down. The window barely opened. Even going to the toilet had to be supervised.

And then there were the other patients. ‘It was like living in hell,’ he recalls. ‘There were some very sick people I came across.’

When he was discharged three weeks later, he believed the worst was over… but another fight was waiting. He says that once home, he was left to cope largely alone, heavily medicated, and unsure how to rebuild his life.

‘When I went back home, they gave me an injection and a bag full of drugs,’ he claims. ‘I mean sleepers and all them different things I had to take to be able to live by myself. Every two weeks, they had to come and give me the injection and I was in the same seat. Just sat there, sunken in. I couldn’t get myself together because the drugs they gave me were just so powerful. I was like a zombie sitting in that chair from injection to injection and I said, “I can’t live like this”.’

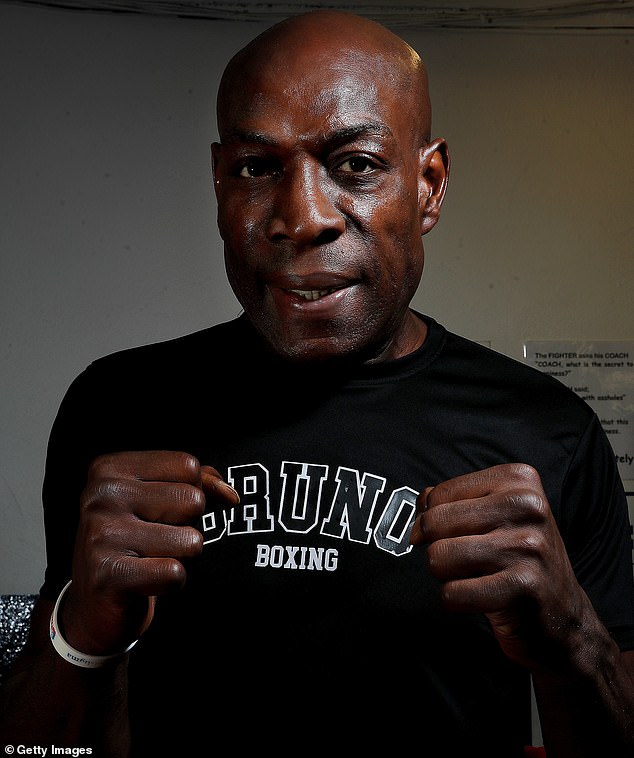

Bruno was Britain’s favourite heavyweight hero in the 1980s and 90s

When he was discharged from hospital, he believed the worst was over… but another fight was waiting

He speaks about the medication not with anger but exhaustion. To come off it, Bruno says he had to prove he could function independently: meaning regular psychiatric evaluations, demonstrating consistent sleep patterns, staying physically active and being closely monitored by his GP and family. He describes it as ‘fighting for my own mind back’ – a slow, stubborn process that took months.

‘They wanted me to be on medication for the rest of my life,’ he says. ‘Tablets and all sorts too. I had to fight it, to not have to take that medication every day. That’s not quality of life. And it’s not just one tablet they want you to take, it’s a cocktail of drugs.’

Bruno won the medication battle and became his own doctor. His rehabilitation would not be medical but physical. He returned to the only routine he had ever trusted: the gym.

‘I am training twice a day even now,’ he says. ‘I’ve got myself a personal trainer and I have three bags at home so I am still boxing. I go to the gym every day for an hour of weight circuits and I make sure I run every day. That could be one hour sprinting or running. All different pieces.

‘Sometimes I’m up at three o’clock at night and I go for a good run. I still do that now. I then make sure I go for a good stretch in the morning, use the steam room and the sauna. I just look after myself. I invest in my happiness.’

When he talks through his routine, you see why it works. For a man who cut himself a generous slice (or three) of birthday cake, he is in striking shape.

His chest is still broad, his arms thick with muscle, his stride balanced and strong. OK, there’s a gentler curve to his waist now – but frankly, he’s earned it. It’s healing his trauma, though, that took years.

‘It was the worst time of my life,’ he says. ‘I never put my hands on anybody after boxing and I was being treated like I was this awful person. After it was all over, I had to go and see a shrink to sit down and talk to them to try and get over what had happened to me. They would give me advice on how I could come to terms with it and it did help getting it off my plate and talking about it.

The decision to section Bruno fractured his family. He has now reconciled with his daughter Rachel, who was just 16 when she was asked to sign the committal papers

‘It was difficult,’ Bruno says. ‘Our relationship is repaired now. I’ve got really good kids’

‘But, when I even think about the way they sectioned me… They’re at my door at night time, they’ve got an ambulance and they’re telling me they want me to be sectioned. I’m not the sort of person to go and cause war with anybody, you know, but they’re set up like I am. I just didn’t want them coming through the house, which is what they tried to do.’

The decision fractured his family. His daughter Rachel, just 16, had been the one asked to sign the committal papers. The family had agreed Frank would never be told who signed it – but he found out anyway. He says that broke something.

Rachel, meanwhile, believed she had saved her father’s life. That without intervention, she may have lost him forever. But, to this day, Bruno says it felt like he was being pushed away.

‘That was difficult,’ he says. ‘Our relationship is repaired now. I’ve got really good kids. I’ve given them a lot of hard, stressful times, doing crazy things and they’ve always tried their best to look out for me. I love them and I know that they love me too.

‘But, I don’t think the sectioning was out of love. Because my daughter refused to come and see me, my son refused to come and see me. It was only Nicola that came to see me, my first child. She’s a good girl. She’s a day nurse, she knows what to do. I just couldn’t understand why they had done this to me. But I love all of my kids and we’ve rebuilt since then.’

Yet even now, there is one silence he cannot quite get past. The British Boxing Board of Control, he says, never picked up the phone.

Not when he was sectioned. Not when the headlines were vicious. Not when the jokes were being made on television. Not when the world was laughing at the man who once carried it on his back.

‘Think about all the millions these boxers have made them,’ he says, shaking his head. ‘The least they could do is put some aside for an old people’s home just for the boxers. The boards don’t give a s*** about the boxers.

Bruno at Ricky Hatton’s funeral earlier this year. He is critical of the lack of aftercare given to boxers by the British Boxing Board of Control

‘Think about the millions these boxers have made them,’ he says. ‘The least they could do is put some aside for an old people’s home’

‘They are the ones going out and doing the boxing and taking all the risk but they don’t give a monkey’s about what happens to them. Boxers have died. They (the Board) don’t deserve the money.’

His voice hardens. This part, clearly, still stings.

The Board has faced similar criticism in recent years – the late Ricky Hatton among those who called for structured aftercare, highlighting the difference between boxing’s support network and the PFA in football.

The Board has always maintained that the responsibility sits with promoters, managers and medical staff collectively. But to Bruno, the principle is simple: boxing makes money from broken bodies. It should be there when the damage shows.

And there are still old wounds from the ring, too.

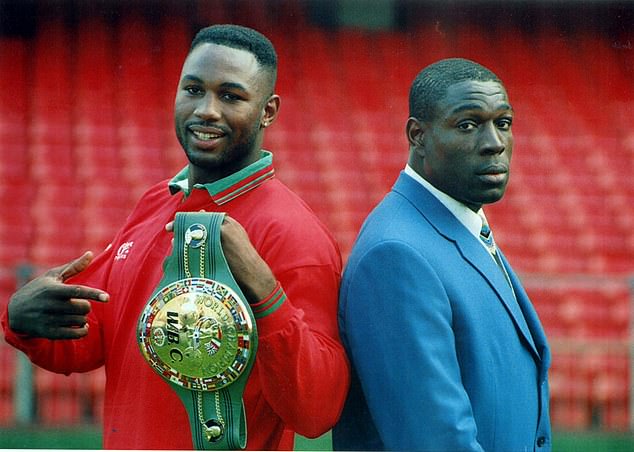

Mention Lennox Lewis and something shifts in Bruno – not anger exactly, but he’s colder. There is history there: two fights, decades of public rivalry, and the infamous press conference accusation in 1993 where Lewis called him an ‘Uncle Tom’. Bruno has never forgotten.

‘We sat down together on the Four Kings documentary 30 years on – it looks very awkward on screen and that’s because it was,’ he says. ‘He was showing off when we were out there. He was going, “Frank, do you want the rematch?” in front of all the boxers.

‘For me, I mean, he’s not right in the head. I don’t have a relationship with him. I don’t really like him. I don’t really dig him. He’s a snake. It’s horrible what he did. He was a grown man saying that (the Uncle Tom jibe). Not a kid. A grown man. I will never let it go.’

Bruno pictured with Lennox Lewis in 1993. ‘I don’t have a relationship with him,’ Bruno says. ‘He’s a snake’

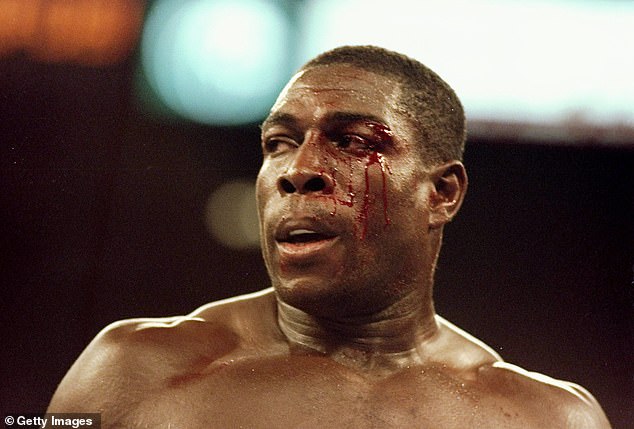

Mike Tyson connects with Bruno in their 1996 world title fight, which Tyson won via technical knockout in the third round

Following his victory over Oliver McCall in 1995 to become heavyweight world champion at the fourth attempt, Bruno should have been on top of the world. Instead, he broke down on camera, pleading that he was not an ‘Uncle Tom’.

Even in triumph, the slur cut deep, overshadowing the hard-won title – a moment he blames Lewis for dampening.

From there, the conversation turns, as heavyweight conversations often do, to size, strength, and the ghosts of eras past. Bruno alleges that some of the American heavyweights he faced used performance-enhancing drugs, though fighters like Evander Holyfield and Mike Tyson have always strongly denied it and have never failed any tests.

‘I know some people that were definitely on drugs,’ Bruno insists. ‘You know what the strength of a human being is like when you go into the ring, and then someone comes in like a gorilla? The guy I am talking about was very, very, very scary.

‘I didn’t know for sure at the time but I had feelings. The Americans were kings at it. The likes of Holyfield, Mike Tyson, whoever – some form of enhancing drug. I am ready to put my thing on the line saying that. I mean they have to have done it, given their body shapes, you know?’

Bruno still keeps a close eye on the sport today. He wants to see Anthony Joshua fight Tyson Fury – Britain’s two giants, finally meeting at the summit.

‘I think it should happen,’ he says. ‘I like Anthony Joshua and I would like him to win against Tyson Fury, but Tyson is one slippery dude. A very clever boxer. Look what he did in those three fights against Deontay Wilder. Wilder could punch like a mule, and Fury schooled him three times.’

The fight, however, hangs in limbo. Fury has retired and unretired multiple times over the past few years, leaving the public frustrated and unsure if it will ever happen. Bruno understands why fans are impatient, but he attributes it to Fury’s bipolar condition.

Bruno after his famous heavyweight title fight victory over Oliver McCall at Wembley in 1995

Bruno with Tyson Fury, whom he says is ‘good for boxing’ and ‘a very clever boxer’

‘It’s because of his bipolar,’ he says of Fury’s retirement U-turns and the disorder he has been diagnosed with. ‘He’s unfairly judged because of that. He changes his mind every week. That’s what bipolar does. But he’s made a lot of money and sometimes his wife has to pull the reins back. I rate Tyson Fury. He’s good for boxing.’

And then, just as quickly, the mood softens again. Bruno stands to make another tea; two sugars, same as earlier. Someone cracks a joke and that great, rolling laugh – the one that fills hallways – is back.

Sitting with Frank Bruno, you are struck not just by the stories he tells, but by the person telling them. He is a man who has faced pain, public scrutiny, and near-breakdown, yet he carries himself with the kind of confidence and warmth that makes it impossible to see him as anything other than a true icon.

Frank Bruno has survived the ring. He survived what came after it. And he is still here – laughing, moving, living entirely on his own terms.