PUBLISHED January 25, 2026

LAHORE/ KARACHI/ PESHWAR:Trigger warning: This story contains references to suicide and self-harm. Suicide is preventable. Please read with care.

They say youth is the gift of nature. What, then, does it say about a society that corners its young into giving that gift away forever?

On December 19, 2025, Muhammad Awais Sultan, a 22 year old fifth semester Pharm D student at a private university in Lahore, died by suicide after falling from the fourth floor of his campus building. Classmates say Awais had been struggling to meet attendance requirements and had approached the administration multiple times, asking for leniency. His requests were refused.

Following his death, students protested, asking for investigation into the case. The university promised an initial inquiry report within 15 days. But weeks have passed, and there is still no report.

When students attempted to speak about their friend and possible reasons for suicide, especially academic pressure, they were shut down, with comments such as, “He must have been going through something personal.” This phrase reflects a larger societal attitude towards suicide. It individualises the tragedy, empties it of context, and allows the institution to move on with impunity.

Students who protested for Awais were ridiculed and infantilised, treated as unruly children rather than concerned peers who had lost a friend and classmate. In the weeks after Awais’s death, suicide became a joke in everyday academic parlance. Students report being taunted for getting low marks with remarks such as, “Ab tum to suicide nahi kar lo ge is par? [You won’t kill yourself over this, will you?]”

To placate anger, the university announced minor concessions: reduced fines for missing student cards and lower OPD medical charges. There was no campus wide dialogue, no trauma informed response. Students demanding answers were met with strict measures. In a space that should have allowed careful listening, for processing collective grief, hostility and indifference prevailed.

Within weeks of Awais’s death, another student at the same university, tried to take her own life. “If the first case had been taken seriously,” said Ahsan Javed, a student leader involved in university protests and negotiations, “perhaps the second could have been avoided.” The idea that suicide is contagious is often invoked to justify silence. However, in this case, silence, it appears, is itself part of the risk.

The choice of language, or the lack of it, around suicide discourse on campuses is telling. It borrows from criminality, emphasising criminal intent, leading to shame and stigma, rather than care and understanding. In fact, for decades, suicide in Pakistan was legally a crime. Attempted suicide remained punishable under the Pakistan Penal Code until 2022 when it was finally decriminalised. The legal shift, however, has not translated into a societal shift. Suicide continues to be treated as a moral failure and a religious transgression. Students describe being met with admonitions like, “Allah gunah de ga [God will punish you],” instead of concern, as moral policing predominates attempts towards changing attitudes.

“Despite decriminalisation, not much has changed structurally,” said Ahsan Mashhood, a DPhil student at Oxford University who is studying suicide from a public health perspective. He noted, “Stigma remains extremely enduring.

Universities continue to treat suicide as an individual crisis, disconnected from its social, cultural, and economic determinants.”

Dr Amna Butt, a clinical psychologist with 17 years of experience, helped establish Beaconhouse National University’s counselling department. “Pakistani universities are not designed to maintain student wellbeing,” she observed.

Most interventions, she explained, are reactive. Institutions respond to crises only. There is little emphasis on psychological education, prevention, or early intervention. “Our system only caters to breakdowns,” she said, “not to the conditions that produce them.”

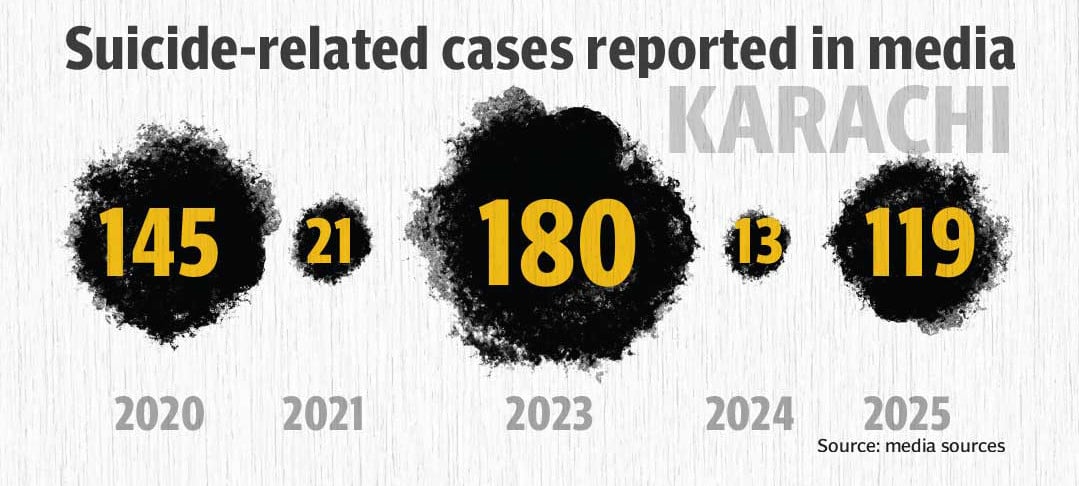

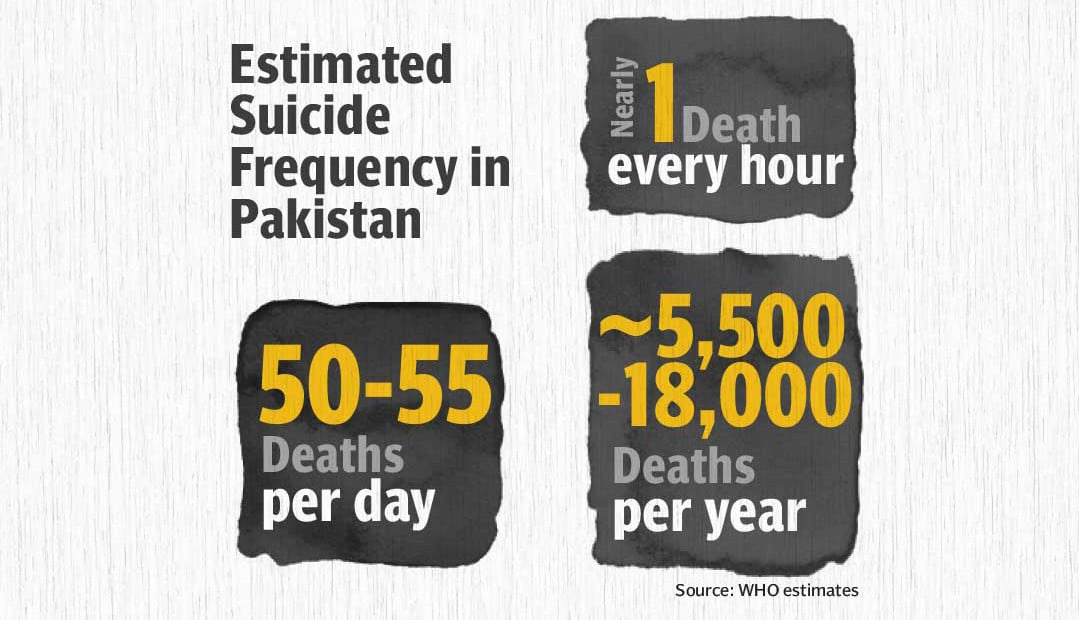

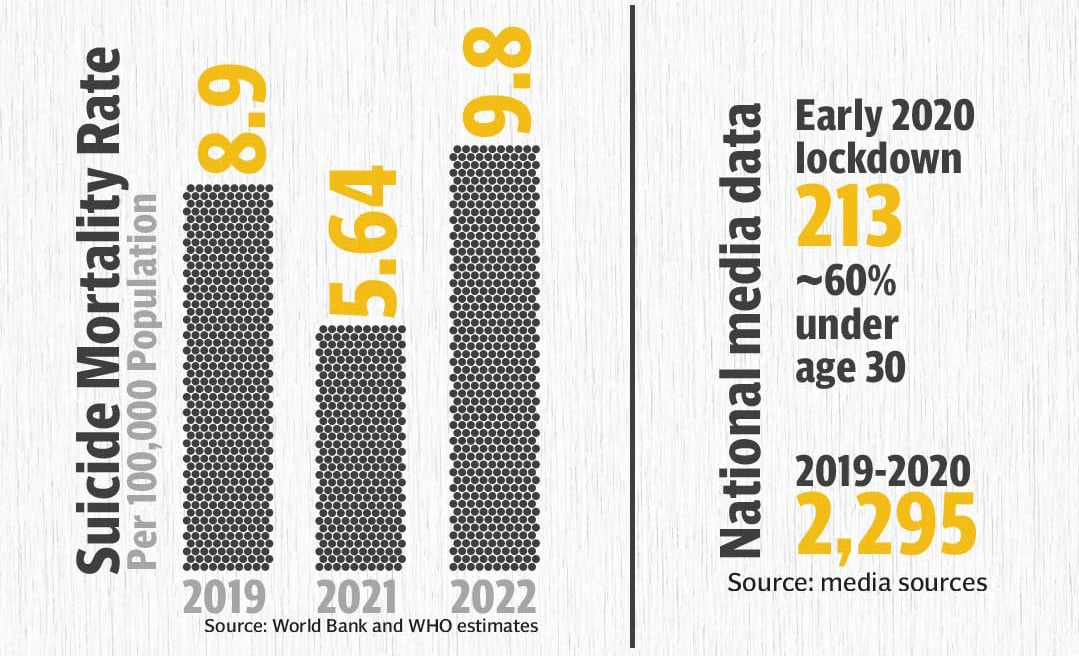

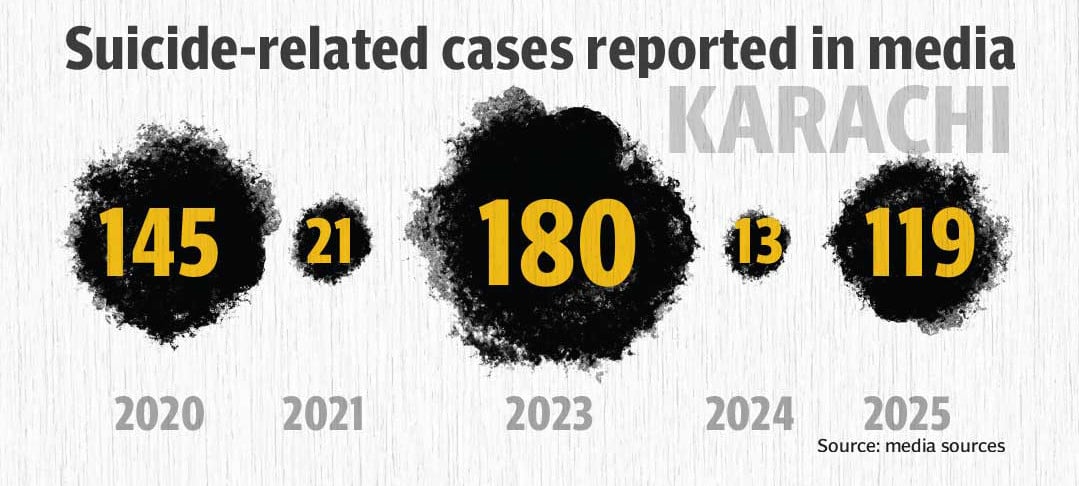

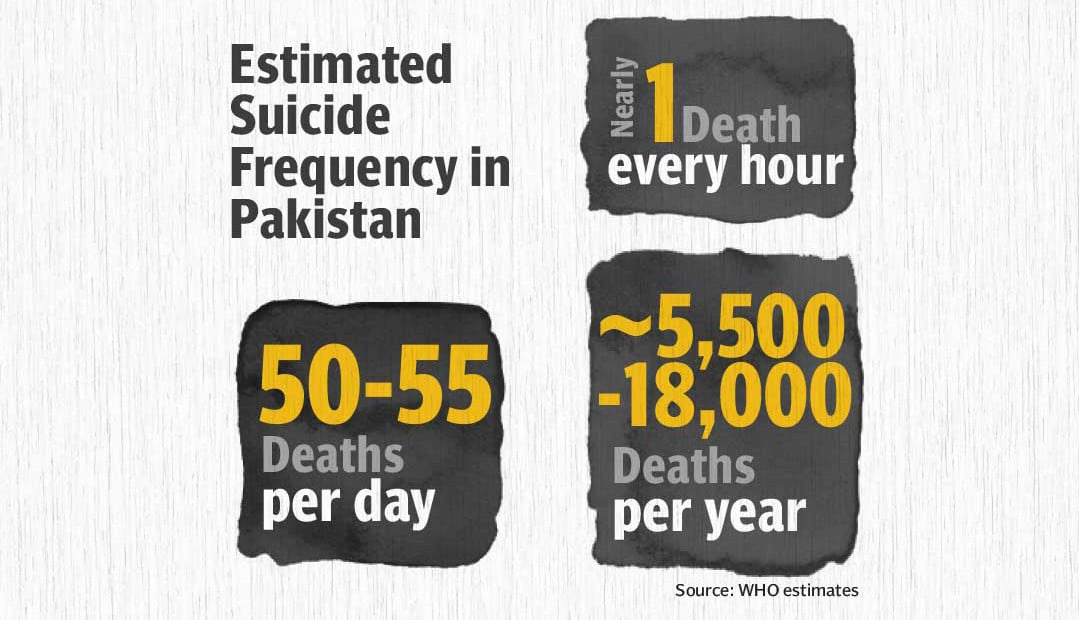

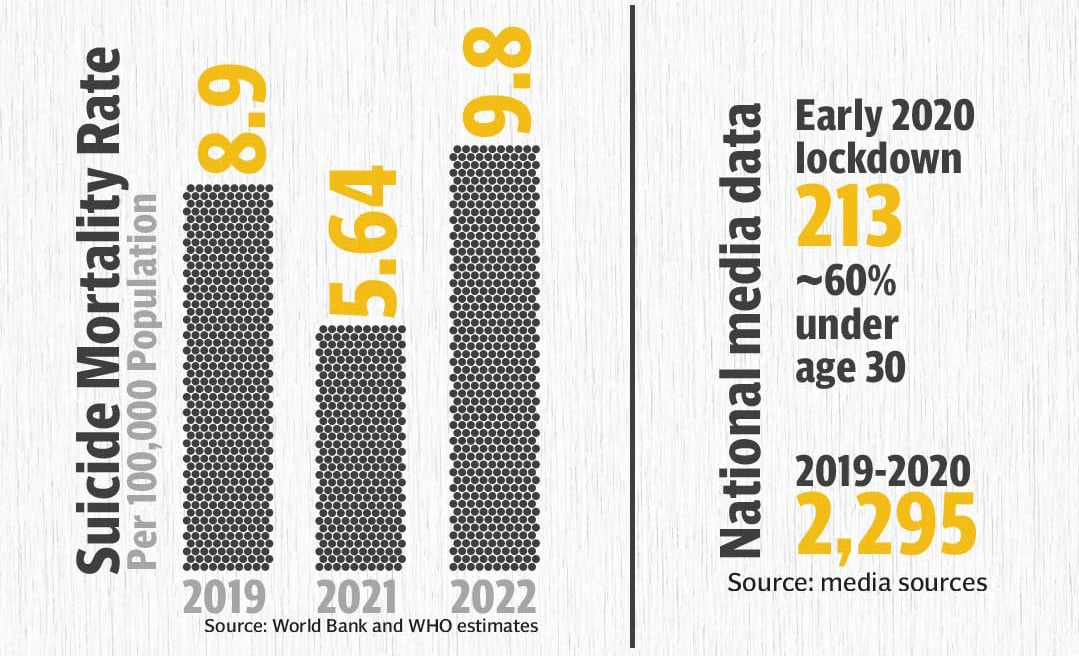

The mental health crisis, especially the rise in suicides, is deeply worrisome. The National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey conducted in 2022 found the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in Pakistan at 37.91%. In 2022, Pakistan’s suicide mortality rate had climbed to 9.8 per 100,000 population, continuing an upward trend. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates, around 50-55 people die by suicide each day in Pakistan, and about 70% of these deaths are among young people aged 15-29, making Pakistan an at-risk country for suicides.

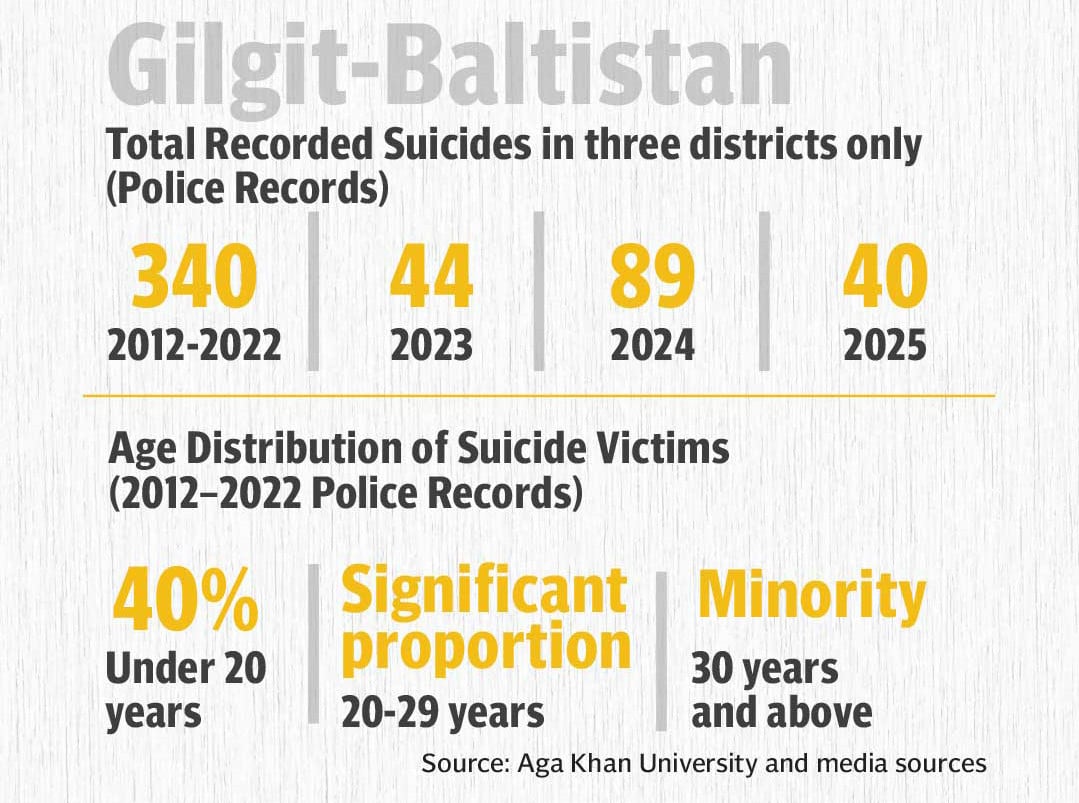

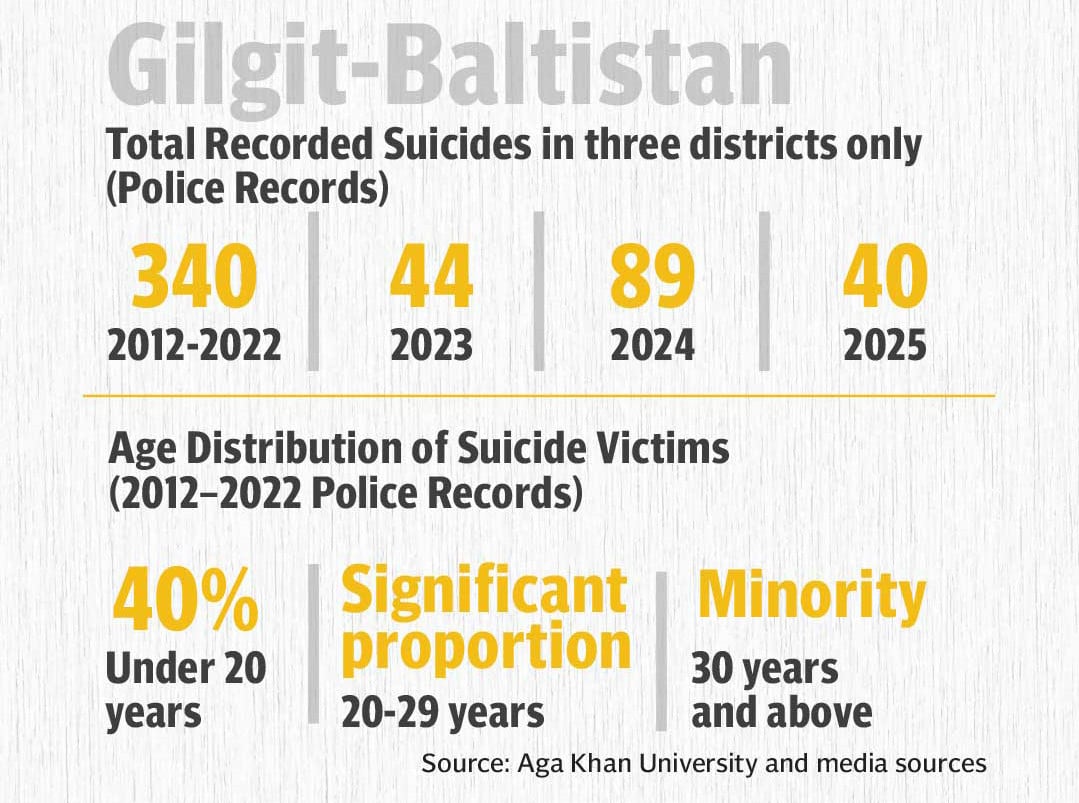

According to some estimates, at least one person takes their life each minute in the country. As per a study by Aga Khan University (AKU), police-record data from three districts in Gilgit-Baltistan show 340 suicides between 2012 and 2022, with 40% of victims under age 20. Even these numbers, Mashhood contested, are highly underreported.

What makes meaningful intervention harder is the near total absence of reliable data. Pakistan has no comprehensive national database tracking suicides, let alone student suicides, or their ideation. To date, neither the police department has compiled a record about this, nor has any NGO come forward in this matter. The few media reports that surface remain far underreported in number. The country also does not conduct psychological autopsies, leaving families, researchers, and policy-makers without insight into why someone took their life.

This absence of data allows universities to frame deaths as isolated incidents, rather than as symptoms of hostile environments. “Universities are also deeply forgetful,” Mashhood noted. “They want to move past these cases as quickly and quietly as possible to protect their reputation.”

Pushed into isolation

For students in Pakistani universities, their mental health has been pushed to rock bottom. By the time a student reaches out for help, the system has already trained them not to expect much in return.

Indeed, the country lacks infrastructure for tackling the mental health challenge it faces. Currently, Pakistan has approximately one psychologist for every 360,000 people, far below the WHO benchmark of one psychologist per 100,000 people, as per sources. Across the country, nearly 90% of universities lack mental health professionals, according to The Express Tribune investigation. Punjab University, with over 55,000 students, has a single counsellor.

Even where mental health infrastructure exists, it is limited, and not many are aware of it. Counselling centres are announced on websites, circulars are issued, and seminars are held. But access remains elusive.

Qazi Shahryar, an MPhil student at a public university and one of the student leaders of the Progressive Students’ Collective (PSC), recalled the exhausting and bureaucratic process of trying to seek mental health support during his undergraduate years at Punjab University. He filled out numerous forms, but ended up getting general advice, which was not very helpful.

“It appears that most students do not even have a right to struggle,” said Amna Abdullah, a fifth-year medical student at a government institution, especially relating to medical students who have recurring exams. The most common statement thrown at them is, “If you can’t cope, then this field is not for you.”

Here, Mashhood observes, “Even well-endowed universities do not have quality care, with only one or two therapists. There is no licensing body in Pakistan, which means many therapists do not meet minimum standards, and often reproduce problematic advice under the guise of therapy.”

This gap between claims and access produces a particular kind of loneliness. Students begin to doubt not only institutions, but themselves. Shahryar described how these layered barriers – first society, then family, then one’s own hesitation – all in the backdrop of increasing state suppression, add to mental pressures.

Even basic safety measures are missing. Dr Butt noted the absence of cameras or protective infrastructure in high-risk areas such as rooftops and stairwells. Pre-existing mental health conditions are rarely identified when students enter university, allowing anxiety and depression to escalate unchecked.

Late payment of fees, she mentioned, is another silent warning sign as the student is then singled out. There is ample shaming involved in the process, and students are barred by the registration office, leading to distress, without an outlet or supporting body.

Academic design compounds this isolation. She expressed that relative grading systems turn classmates into competitors, due to which collective study, shared notes, and collaborative learning have become limited. “You ought to make friends in university,” Dr Butt observed, “but you are now competing against them.” Burnout follows quickly, especially within packed curricula that leave little room to breathe.

Hyper-connectivity adds another layer of risk. Dr Butt shared cases where students, unable to speak to peers or faculty, turned to online tools, particularly AI platforms, to search for painless ways to die. This is not a failure of technology, she argued, but of human listening. Mashhood echoed similar observations, “It is heartbreaking to see the rising trend of students talking to robots instead of opening up to friends.”

According to Dr Butt, international practices follow a tiered approach: prevention through education, early identification of risk, and accessible clinical care. Pakistan, by contrast, is in dire need of updating its system. “Our notions on mental health are from the 19th century, our academics are from the 20th century. There is a two-century backlog,” said Dr Butt. “Our systems need major updating, and HEC must admit this.”

Mental health is treated as a luxury, not a basic need. Care providers themselves are exhausted, underpaid, and overwhelmed, she shared. “There needs to be more awareness of the fact that mental health is not a permanent state. It can be improved. More importantly, suicide can be prevented,” she added.

Shahryar, pointing out the impacts of this isolation, stated, “In South Asian countries, Gen Z is leading change in society. Take the example of India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. But here, it has been over 40 years since the ban on student unions. They only face crackdown after crackdown from teachers, families, institutions, and the state.” He called for the reinstatement of student unions in an attempt to empower students.

Administrative cruelty and forced forgetting

Students across public and private universities describe institutional life as increasingly governed less by education than by discipline, where the focus remains on enforcement of attendance records, collection of fines, and the use and misuse of authority in humiliation.

In the aftermath of Awais Sultan’s passing, this cruelty became apparent. Students who organised protests or raised questions about administrative responsibility were met with retaliation. Ahsan was removed from his elected position as president of the Kashmir Students Society, and so was his general secretary, due to protests which were deemed as “haraam”.

Students involved in protests say they were stopped repeatedly at campus gates, forced to make unnecessary rounds of the premises, and subjected to verbal intimidation. Videos of student organisers circulated on WhatsApp groups populated by administrative staff and faculty, where some students were labelled RAW and BLA agents and sympathisers. Such false accusations in our political climate carry a dangerous threat to life. “This entire process added another layer of trauma,” Ahsan said.

Administrative cruelty has become the normal academic practice, especially in public universities. Students describe receiving exam notices barely two hours in advance, being denied reassessment without explanation, and being summoned to offices only to be verbally abused.

Ahsan recalled requesting a two-mark increase that would have changed his grade.

Instead of a review, he was called into an office where four professors were waiting. One shouted curses at him, another threatened to fail him outright. “It was mental torture,” he said, even though the professor passed him.

This culture is reinforced by an institutional preference for forgetting. Once immediate unrest subsides, administrations move swiftly to restore normalcy. There are no memorials, no sustained conversations, no policy revisions grounded in reflection. Suicide becomes a question of the university’s reputation, one of the main reasons why such cases are rarely reported, particularly in private universities that silence questions.

Economic precarity intensifies this cruelty. Constant fee increases, late-payment penalties, and public shaming at registration offices disproportionately affect working-class students. Shahryar described decision-making on campus as arbitrary guesswork shaped by power. “Students have been robbed of their agency. There is a lot of hopelessness,” he said.

Neoliberal restructuring has further shrunk community spaces for students. As public funding has reduced and universities chase private partnerships, subsidised community spaces disappear. At Punjab University, a decades-old dhaaba, that once provided affordable food and a place to gather, has been replaced by a private pizza outlet. The loss signals the decrease in support systems, Shahryar explained.

Gender and power imbalances

While female enrolment has increased, positions of power in universities remain overwhelmingly male: senior faculty, hostel administrations, disciplinary committees, and grievance bodies are dominated by men who control academic progression, access to housing, and institutional decisions.

Laiba Imran, a fourth year Economics student from a public university, said, “Gender discrimination is normalised in class and on campus. If you speak against it, the admin or faculty takes revenge by docking off attendance marks or some other way.”

Comments like “auratain ghar basanay ke liyay hoti hain [women are responsible for homemaking]” are bandied about. Religious idioms are commonly used to justify problematic opinions. “Female students are even afraid of going to male professors’ offices,” she added.

Another student, requesting anonymity, shared that misogyny is not surprising.

Even cases of sexual favours have become widespread. She shared an instance where the warden agreed to assign her the requested hostel in return for intimacy.

Female students who report harassment or psychological distress often encounter deflection. Complaints are undermined by interpersonal misunderstandings and emotional instability. Rather than opening room for genuine conversations and impartial investigation, disclosure frequently initiates scrutiny, creating an environment of mistrust and suspicion.

“Power imbalances remain against our favour, especially when it comes to evidence of harassment or misconduct,” Laiba shared, citing an example where a professor placed his hand on her female friend’s head and ran it down her back, pretending it was a paternal gesture. When students express discomfort, they are occasionally told not to misread intentions and are reminded of the professors’ seniority.

At another occasion, after repeatedly approaching university authorities for three months to hold an advisor accountable over a sexist WhatsApp text, she found herself navigating a maze of discouragement. In the end, nothing happened. It was she who got exhausted, and even her academic performance plummeted.

A culture of harassment has seeped deep, but in the absence of any accountability and data, students of a private university circulated a student-led Google survey. According to the survey, 62% of students experienced any sort of harassment on campus, out of which three-quarters identified faculty or administration as the harasser.

Environment of fear

Amna described medical school as a place where “your identity is defined by grades and marks.” Falling behind is a total failure rather than part of a learning journey.

Students who get a ‘supplee’ or are demoted to a junior batch often disappear socially. “They feel most secluded,” she said, “as if everyone is judging them for not being smart enough.”

“Depression and self-harm are very common,” Amna noted, “to the extent that joking about them has been normalised.” Students casually use benzodiazepines, Xanax, and SSRIs, often without prescriptions, taken weekly, sometimes daily, just to survive weekly medical exams. Fear settles into their bodies: trembling hands before results, nausea outside examination halls, and the constant sense of impending doom haunts students, especially on the day before exams.

Amna recalled hearing of a student who jumped from a campus building after failing an exam. The story was swiftly buried. No inquiry followed. Students were instructed not to speak. The administration acted as though nothing happened on the campus.

Laiba also observed that some exams appear “specifically designed to fail students.” Evaluations have become less about knowledge and more about obedience.

In such spaces, students learn to internalise blame and keep moving until they cannot.

“Our system is built for neurotypical default students,” Dr Butt reinstated, “and those who actually need help even suffer to look for it because of this inbuilt design. Our focus is on students who are already excelling.”

Mashhood noted, “We do not have a suicide hotline. The one we had has gone out of service.” But the problem, he pointed out, is its number still shows up when anyone searches suicidal thoughts or ideation on the web. When they click on the number, no one picks up. This is extremely harmful as it reinforces the same pattern that no one is listening to the person who needs help.

Mashhood recommended that the best thing to say to someone who is struggling with suicidal ideation is not to remind them that life is worth living or that it will get better. Instead say to them: “I am here for you.” Be attentive to their worries. Listen.

With additional reporting from Wisal Yousafzai and Muhammad Ilyas