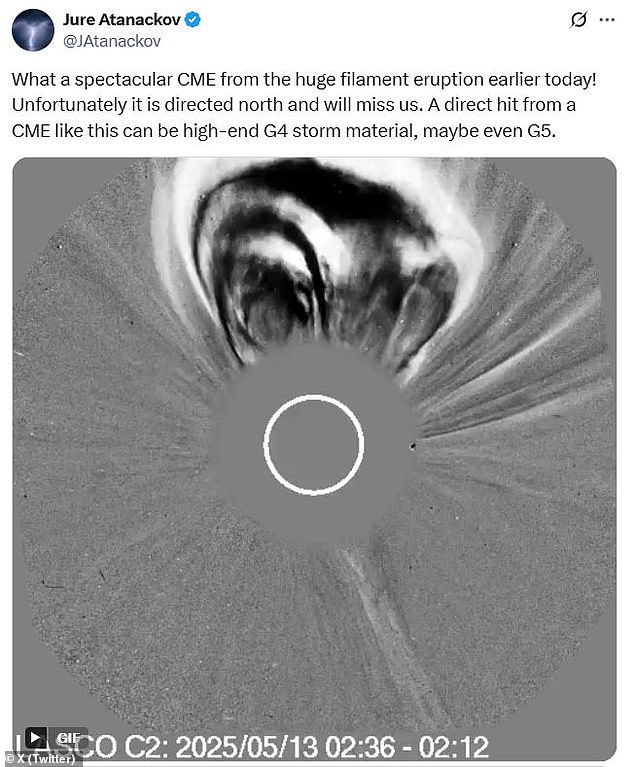

On Tuesday, astronomers watched in amazement as a vast ‘bird wing’ solar eruption tore away from the sun’s surface.

At 600,000 miles long (one million km), a direct hit from this filament of superheated plasma and charged particles could have caused a severe or even extreme geomagnetic storm.

Thankfully, scientists have now confirmed that Earth has escaped with, at worst, a glancing blow from the massive storm on Friday morning.

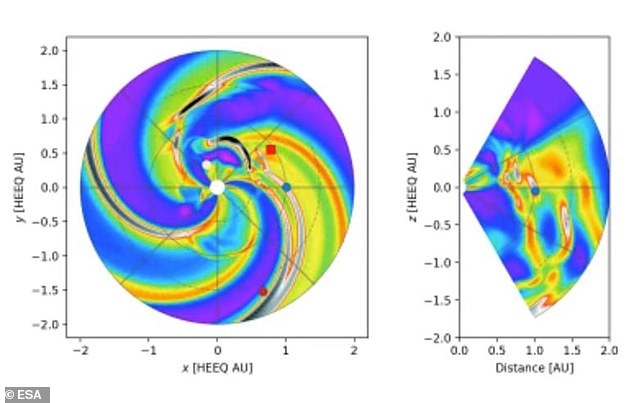

In this incredible video created by the European Space Agency (ESA), you can see how the planet narrowly dodged a direct hit.

That means there will not be any disturbances to electronic equipment or radio communications services that solar storms can trigger.

However, as the wake of the filament eruption passes Earth, astronomers say there could be a small chance of spotting the Northern Lights over the UK on Friday night.

As charged particles from the sun collide with the atmosphere, they transfer energy to gas molecules, causing them to glow in an effect we see as the aurora.

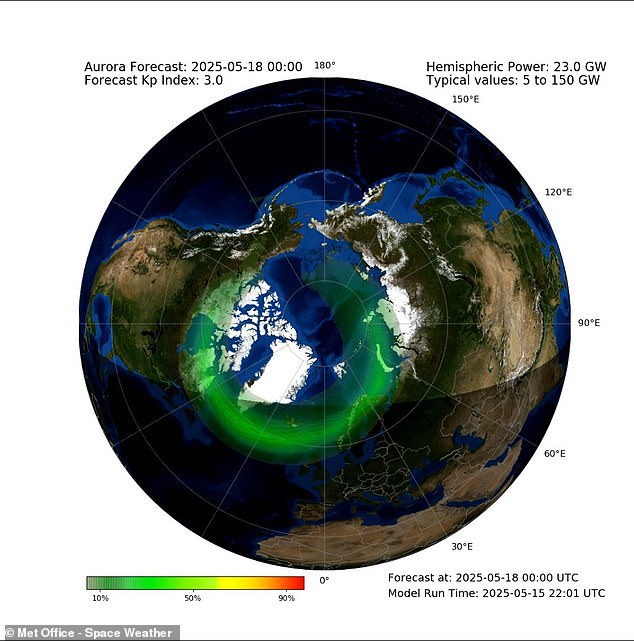

According to the Met Office’s space weather forecast, a glancing blow means some of that stunning glow could be visible as far south as parts of Scotland.

The European Space Agency’s space weather simulations have revealed just how close Earth came to being hit by the ‘bird wing’ solar eruption. In their video, Earth is shown as a blue dot as the flares are sent from the central point, the sun

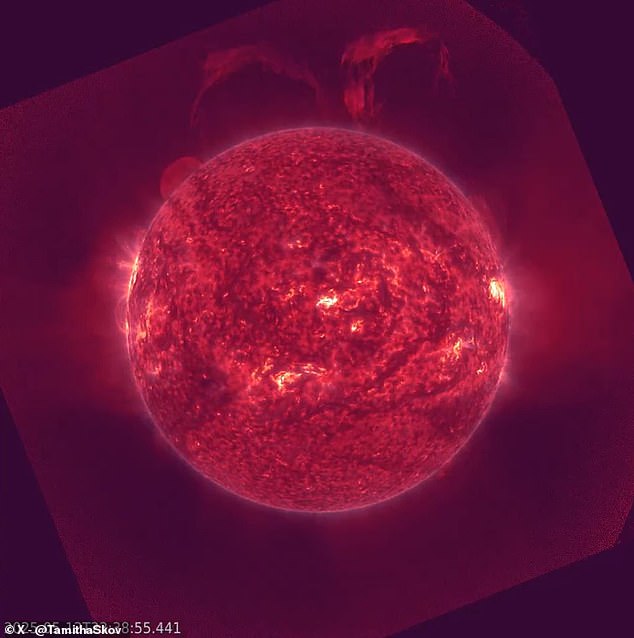

On Tuesday, astronomers spotted a 600,000-mile-long (one million km) filament eruption tearing away from the sun’s surface, sparking concerns that the eruption might cause geomagnetic storms on Earth

The event which is currently causing minor geomagnetic activity above Earth is something called a filament eruption.

Unlike solar flares, which are bursts of high-energy radiation, filament eruptions involve huge waves of solar particles.

Professor Sean Elvidge, an expert on the space environment from the University of Birmingham, told MailOnline: ‘Filament eruptions, also known as Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), occur due to instabilities in the Sun’s magnetic field.

‘These instabilities trigger large-scale expulsions of magnetic field structures and plasma into space. These eruptions vary greatly in speed and size, some rapidly traveling outward at nearly 3000 km/s.’

During an eruption, filaments of cooler plasma become suspended above the sun’s surface by powerful magnetic fields.

In images of the sun, you can see these filaments as long, dark sections shifting over the surface.

But when the magnetic fields weaken, these filaments can suddenly break free in a violent eruption.

It is the arrival of these waves of material in the CME which triggers geomagnetic storms and enhanced auroral activity on Earth.

Had the full brunt of the storm collided with Earth, one aurora chaser on X predicted that it could cause a ‘G5’ or extreme level magnetic storm

On Tuesday, solar observation satellites captured the moment two enormous filaments broke away from the sun’s northern hemisphere in an eruption that sent a CME hurtling out into space.

As the filaments peeled away from the sun, they crossed into a sweeping structure resembling a vast pair of bird wings.

In a post on X, aurora photographer Vincent Ledvina wrote: ‘Not sure what to call this eruption, maybe the “bird-wing” or “angel-wing” event? Either way, it is truly something to witness!’

In the ESA’s solar wind forecast, you can see the moment that the ‘bird wing’ solar eruption emerges, with the darker yellow and red regions showing areas of denser plasma and more intense magnetic fields.

As this video shows, most of the material ejected from the sun was shot out of the northern hemisphere safely away from Earth, which is shown as a blue dot.

Juha-Pekka Luntama, head of the space weather office at ESA, told MailOnline: ‘The forecast for this CME was that it might give a glancing blow today, but most likely it would pass above and ahead of the Earth.

‘So, the expected impact would be small or nothing at all.’

However, a small amount of the solar material has made its way to Earth, catching our planet in the wake of more intense magnetic fields.

As the filaments peeled away from the sun, they crossed into a sweeping structure resembling a vast pair of bird wings

Luckily, the eruption mainly ejected from the sun’s northern hemisphere and away from Earth. That means the planet was only struck by a very minor glancing blow on Friday morning

The Met Office predicts that there is a small chance of seeing the Northern Lights over Scotland this evening as the wake of the coronal mass ejection passes

Professor Elvidge says this would be, at most, a ‘minor interaction with the edge of the event’, yet the size of this interaction means that any major disturbances are unlikely.

Krista Hammond, space weather expert at the Met Office, told MailOnline: ‘Because of where this left the Sun, the vast majority of the material will miss Earth.

‘This means that even if we do receive a glancing blow from the eruption, it will be weak – a minor geomagnetic storm at most – which will not have any significant impacts.’

Slightly elevated geomagnetic conditions may persist for the next 24 hours, but these will soon abate as the wake of the CME passes.

At most, the Met Office predicts ‘a low chance of the aurora becoming visible down to northern Scotland and similar geomagnetic latitudes, where viewing conditions allow.’

Yet, had the full force of the CME collided with Earth, the situation may have been very different.

Professor Elvidge says: ‘If the CME had directly impacted Earth, it could have triggered stronger geomagnetic storms, possibly resulting in disruptions to power grids, interference with GPS systems, and increased satellite drag which can lead to a greater risk of satellite collisions.’

In some cases, the currents generated as CMEs interact with Earth’s magnetic field can temporarily block out radio communications and satellite navigation in certain areas.

In extreme scenarios, these currents can be so powerful that they overload electrical infrastructure, damaging the power grid and railway lines, and even sparking fires.

However, events on that scale are extremely rare and have only hit Earth a handful of times in recorded history, such as during the 1859 Carrington Event.