That Monday morning couldn’t have started out more perfectly. After waking to glorious autumn sunshine, my husband Charlie and I walked our two eldest children to the school bus stop to wave them off.

Refreshed after the weekend, I remember thinking: ‘It’s going to be a great day.’

Charlie kissed both kids on the head and told them: ‘I love you.’ Then he headed off to work. I was distracted in that moment, chatting on the phone as we briefly hugged, then I waved him goodbye.

But it was the last time I’d ever see Charlie alive. Within a few hours, my world would be shattered to smithereens.

Later that morning Charlie, 32, entered a school and shot dead five young girls, injuring another five, before he turned the gun on himself. His actions left me in tumult, trying to reconcile the loving man I’d been married to for ten years, the father of my three young children, with someone who could carry out such a despicable crime.

Almost two decades on, my tears still fall for the families whose daughters never came home and the children who escaped but will always live with the trauma. One of the girls who survived, six-year-old Rosanna King, was left in a wheelchair and unable to talk after Charlie shot her in the head. She died last year, aged 23, as a result of her injuries.

I have wrestled with shock and grief, with unanswered questions and self-recriminations. Could I have somehow known what my husband was about to do? Should I have been able to prevent a tragedy that shattered so many lives?

Now 47, there are many labels I carry with pride: mother, daughter, friend. But because of what Charlie chose to do, ‘wife of a school shooter’ will always be listed among them.

Charlie and Marie met at church and married two years later

I first met Charlie at church when I was 17 and he was 20 and immediately liked his quiet, gentle nature. While he rarely talked about his emotions, Charlie’s kindness always shone through.

Two years later I was saying my vows, certain that I was committing myself to a wonderful man. When I discovered that I was pregnant the following spring we were delighted. Then, at 26 weeks, I went into labour. Our beautiful daughter Elise only lived for 20 minutes. We were both devastated but Charlie didn’t talk about it and I never pushed. I wanted him to process things in his own way.

Having our second daughter two years later in 1999 helped heal my heart and she was followed by her brothers in 2001 and 2005.

Charlie was a great husband and father, so hands-on with the kids, always coming up with fun games.

Every weekend he would take them to the small store near our house and let them buy a little something, like a lollipop, which they loved.

We had a tradition of buying each other a Christmas tree decoration each year and his were always so thoughtful and special. I still have them. One Mother’s Day he bought me a beautiful rose bush.

As the years passed, he’d occasionally become withdrawn, admitting that he still thought about Elise. ‘I imagine what life would be like if she’d lived,’ he’d say as he watched the children play. ‘Me too,’ I’d reply.

By the autumn of 2006, our life had a slow, happy rhythm.

Marie’s therapist helped her to see that Charlie probably had a psychotic break, a result of well-hidden depression

We lived alongside an Amish community in Georgetown, Pennsylvania. This tight-knit, peace-loving religious community is known for following a 19th century way of life. It was normal for us to see horse-drawn buggies in the supermarket car park or women in bonnets selling pies at the roadside.

Charlie worked for my grandparents, driving milk from their farm to the dairy. We lived next door to them and less than half a mile from my parents. My world was exactly as I wanted it. At that point it was more than enough to be a stay-at-home mum to our daughter, seven, and our sons, five and 18 months.

I’ve mentally combed through the days and months leading up to October 2, 2006, for any signs that Charlie’s mind had gone to a dark place. But apart from a lingering sadness around our daughter, he seemed to be his normal self.

The first inkling that everything was not OK only came later that autumn morning when I heard the phone ring. It was Charlie, except it sounded nothing like him. ‘Marie, I’m not coming home,’ he said, his voice flat and cold.

I felt a chill run through me; it was like listening to a stranger.

Before I could reply he began to speak again in a terrifying monotone that only increased my panic. ‘There’s something I have to do.’

It never occurred to me that he would harm others, only that he might do something to himself.

Petrified, I begged: ‘Please don’t do whatever it is that you’re planning. There’s always another way.’ But it was as if Charlie hadn’t heard me. ‘Please tell our family that I love them,’ he continued. ‘I left a letter for you on the dresser.’ Then he was gone. Dread in the pit of my stomach, I ripped open the envelope.

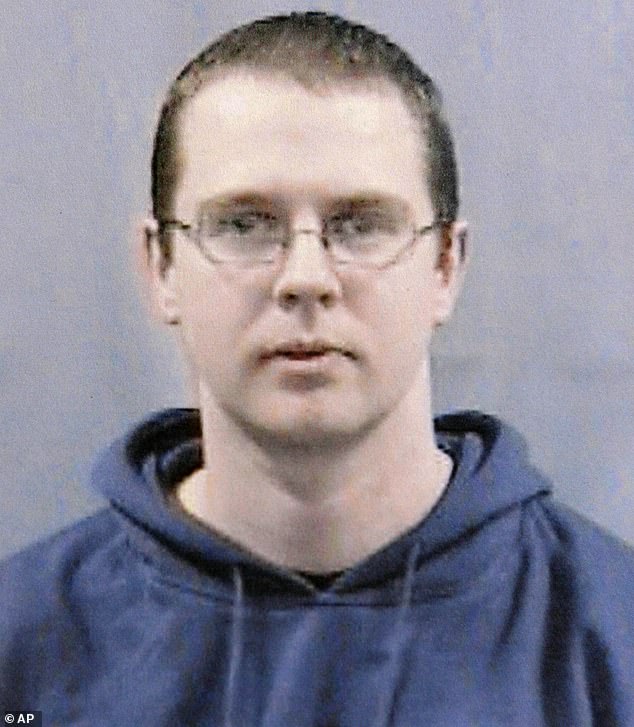

Charlie Roberts had entered a schoolhouse and shot ten schoolgirls before shooting himself

Seeing so many tightly-written pages from a man who never wrote more than a birthday card only increased the feeling that this was a man acting out of character.

Sections of his ramblings leapt out at me. How much he loved me, how much pain he was in from losing Elise. I knew it was a suicide note.

I immediately called the police. Then I rang my mum. ‘Something terrible is happening with Charlie. There isn’t time to explain but I need you to get the kids from school and take them home with you.’

Hearing the panic in my voice she didn’t ask questions. Then all I could do was wait. It wasn’t for long. Almost immediately sirens began screaming in the distance and helicopters appeared overhead.

Yet denial kicked in. Surely this was just a coincidence, wasn’t it? Then the police appeared at my door. ‘It’s Charlie, isn’t it?’ I asked, somehow getting the words out. Seeing them nod I continued. ‘He’s dead, isn’t he?’ Another nod.

I thought of my children and my heart broke. Yet I didn’t know the further horror that was to come. At first their words simply made no sense. They said Charlie had entered a small Amish schoolhouse in West Nickel Mines, a mile up the road.

He’d forced the boys and the teacher out, then locked himself and the remaining ten girls inside. Half an hour later he’d begun shooting.

He’d killed some of the girls and injured others – they didn’t know the exact numbers yet – then Charlie had taken his own life. The girls were aged between six and 13. Two of the dead were sisters.

Marie wrote a memoir in 2013 and graduated with a degree in organisational behaviour in 2020

It was incomprehensible that my loving husband, this wonderful father, could possibly have done this.

But through the physical wave of shock, I knew that what they were saying was true. I was overwhelmed with sadness, for the children and their families, for my own children, for the first responders who’d had to attend the scene.

I also felt absolutely alone, the foundations of my safe life ripped away. ‘What do I do?’ I asked the police officers in desperation. ‘You need to leave your home,’ they said. ‘Go before the news breaks.’

At my parents’ house I sat on the sofa, one child on either side of me and cradling the littlest, trying to think how to break it to them that their innocent, happy childhoods were over. ‘Your dad made some very bad choices,’ I began. ‘And some people got hurt. Some people died and he died too.’

I knew that they would have to hear the whole story soon. For that moment, it was all I could do. Holding them as they quietly cried was heartbreaking.

The phone didn’t stop ringing and friends texted in bewilderment.

No one could believe that Charlie had done this and everyone was asking me to explain why. But none of it made sense.

Then I saw a small group of Amish men walking towards the house.

‘They’re in unimaginable grief and have every right to ask for an explanation,’ I thought in panic. ‘And I have nothing to give them.’ Knowing that Amish men only really speak to other men, my dad offered to talk to them while I nervously waited inside.

Through the window I saw the men put their hands on Dad’s shoulders and then the tears flowing down all their faces.

When Dad walked back in, I expected to hear their rebukes. Instead, he told me: ‘Marie, they came because they were concerned about you.’

This was the one group of people who had the right to express their grief, pain and anger. Instead, they’d come with forgiveness. I sobbed, unable to process the power of what had just happened.

That night, holding my children close, I barely slept. I had no idea how I would support my family financially, help them emotionally process this horror and somehow build a new life for us.

In the nightmarish days that followed the kindness of the Amish community continued to astound me. At Charlie’s funeral, as I desperately tried to keep cameras away from the children, they arrived and formed a circle around us to shield us.

For the Amish having their photos taken violates their religious beliefs and yet they did it to protect us.

When I spoke to victims’ families and visited one of the injured girls in hospital, her parents told me that they worried that while they had one another to lean on, I was all alone. I was humbled by their kindness and generosity.

But while the Amish were incredible, it was clear not everyone felt the same.

One morning a stranger knocked on my door at 8am as I was getting the children ready for school, demanding to know how I could have been unaware of Charlie’s plans. And I knew that the children were facing comments and stares now they were back at school. It hurt me deeply that I couldn’t protect them.

Through counselling I was able to work through the questions whirling through my mind.

My therapist helped me see that Charlie probably had a psychotic break, a result of well-hidden depression. There were no red flags that I’d missed and I wasn’t responsible for his actions.

His friends said the same – that there was nothing they’d seen either that had ever made them think he was capable of this.

Strangely, I didn’t feel anger at Charlie for what he’d done. Perhaps it was self-protection but in my mind he became two different people: the loving man I’d married who’d play with the kids and Charlie Roberts, the man who committed this unspeakable crime. Compartmentalising our relationship also meant I could bear to remember the good times with the children.

I desperately didn’t want them to see their father purely through the lens of his crime.

I began to realise I was so much stronger than I’d ever believed. That I could make decisions that other people might not understand, but that wouldn’t stop me. Which is why, when I began dating a lovely man called Dan, now 57, who I met through friends, I didn’t care about the whispers that it was all too fast.

In my old life the judgment would have been too much to bear; now I knew that so long as my children approved, I could follow my heart. We married the next year.

In the years since, Dan has been a rock. He accepted my past without question and even supported my idea to move the rosebush that Charlie bought me that Mother’s Day into our garden when we moved to a new house nearby after we married. I didn’t want to throw away what was left of the beauty of our lives from before the shooting.

I watched the roses grow as I wrote a memoir in 2013, graduated with a degree in organisational behaviour in 2020, started a consulting company and began coaching. I’m also incredibly proud of the lives my children have forged for themselves, despite what they went through.

While the anniversary of that dreadful day will always be painful, I no longer feel guilt or shame. But I’ve accepted that what Charlie did will forever be part of my story.

I’ve seen that by sharing it, I can help others. People going through their own painful, messy struggles know that I’ll never judge them. And I’m living, breathing proof that despite life’s darkest moments, there is still hope and a future filled with joy.