Archaeologists have proven the existence of a lost ring of pits near Stonehenge, and say it could be Britain’s largest prehistoric structure.

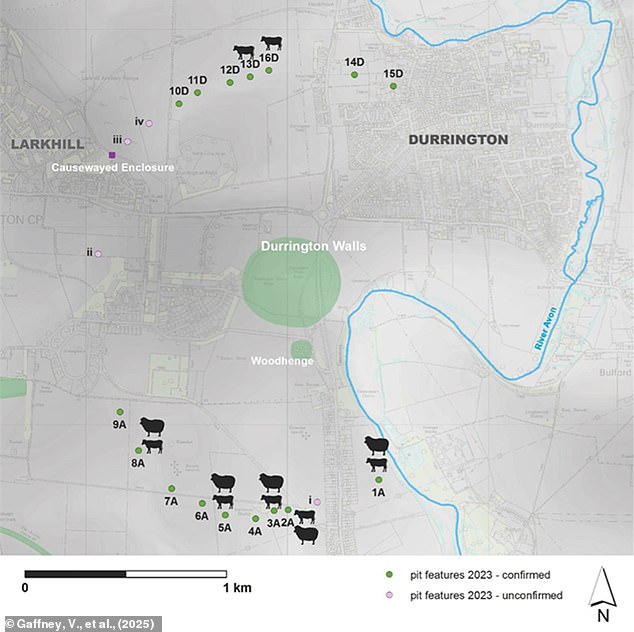

The ring of more than 20 pits, some of which are 10 metres deep and five metres wide, extends in an arc more than a mile across.

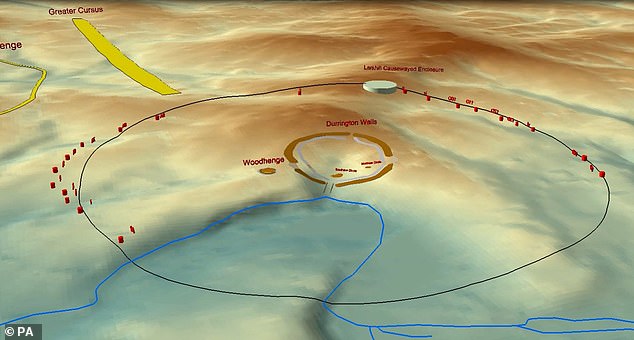

At their centre are the ancient sites of Durrington Walls and Woodhenge, 1.8 miles (2.9 kilometres) northeast of Stonehenge, where the henge builders held ritual feasts.

Using an array of novel scientific techniques, researchers now say that these pits were likely constructed by Neolithic people around 4,500 years ago.

Researchers say that carving the pits into Wiltshire’s chalky ground would have taken an enormous amount of planning and effort.

Lead researcher Professor Vincent Gaffney, of the University of Bradford, told the Daily Mail that the vast structure was a ‘cosmological statement’.

He says: ‘They link Durrington walls henge and another site at Larkhill – a causewayed enclosure about a thousand years earlier. ‘

‘And in doing so, inscribed a boundary into the landscape – setting aside an area of special significance.’

Scientists have proven the existence of a lost ring of pits nearby Stonehenge, which is likely the UK’s largest prehistoric monument

The pits surround ancient sites of Durrington Walls and Woodhenge, 1.8 miles (2.9 kilometres) northeast of Stonehenge (pictured). These sites are believed to be where the Stonehenge builders held ritual feasts

The pits surrounding Durrington Walls were first found in 2020, and were immediately hailed as one of Britain’s most impressive ancient sites.

The discovery of the pit circle appeared to further cement the Salisbury Plane’s reputation as a uniquely important religious site for Britain’s Neolithic people.

This area is not only home to Stonehenge, but also a wider series of interconnected ceremonial structures, stone circles, and cemeteries from the Stone Age.

Durrington Walls, which sits at the epicentre of the pit circle, is a ‘superhenge’ that is believed to be the largest anywhere in the UK.

Likewise, the nearby ‘Woodhenge’ was an enormous timber monument built around 2500 BC, consisting of six concentric rings of posts of varying size forming an oval monument 40 metres across.

However, scientists have questioned whether the pits were really dug by humans or whether they might have been natural features of the landscape.

In a new research paper, titled ‘The Perils of Pits’, Professor Gaffney and his co–authors present a new batch of scientific evidence to prove the pits’ human origins.

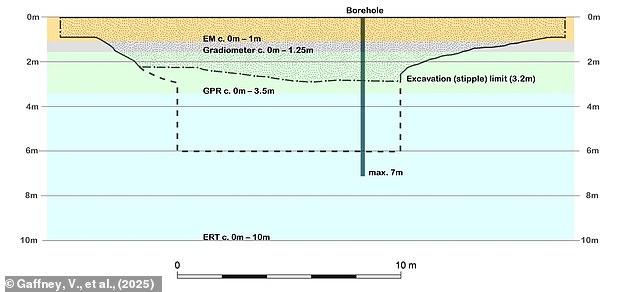

Since no one technique could answer all of their questions, the researchers deployed an array of techniques to work out the exact structure of the pits.

The pits encircle the ancient sites of Durrington Walls and Woodhenge. Woodhenge was an enormous timber monument built around 2500 BC, consisting of six concentric rings of posts of varying size forming an oval monument 40 metres across. Pictured: Stone pillars marking the locations of Woodhenge’s timber posts

Scientists had questioned whether the pits were really man–made. So scientists used an array of scientific tests to work out their exact shape and structure

First, they used a technique called electrical resistance tomography, which measures changes in electrical resistance at the surface to work out the size of underground structures.

Then, radar and magnetic imaging were used to assess their depth and shape.

‘This in itself did not prove these features to be man–made,’ says Professor Gaffney.

‘So sediment cores were extracted and an array of techniques, including novel geochemistry, were used to characterise the nature of the soils.’

‘Optically stimulated luminescence’ was used to work out the last time that the soils were exposed to the sun, and ‘sedDNA’ to extract plant and animal DNA directly from the dirt.

This revealed that each pit had the same pattern of repeating layers, starting in the late Neolithic period – something that would be extremely unlikely to happen naturally.

These techniques also identified the DNA of sheep and cattle, which suggests that the pit circle was being occupied and farmed at the time.

Professor Gaffney says: ‘It confirms that this structure – probably the largest prehistoric monument in Britain at least – is a purposefully constructed monument in a landscape which is itself exceptional.’

The researchers used a technique called electrical resistance tomography, which measures changes in electrical resistance at the surface to work out the size of underground structures (illustrated)

The researchers found that the pits had a consistent pattern of layers and even contained DNA of cattle and sheep. This suggests that they were deliberately built by humans

By showing that these vast pits were carved by humans, the researchers have shown that Britain’s ancient people were much more organised than had previously been believed.

‘The size of the structure demonstrates the society they lived in was capable of planning and motivating large numbers of people for religious purposes,’ says Professor Gaffney.

The pit circle is so large that you cannot see across to the other side, but still traces a near–perfect circle around Durrington Walls.

This regularity suggests that the pits must have been laid out by pacing, which implies that the people of ancient Britain had a numerical system for counting.

If true, this could be some of the very earliest evidence for the ability to count in Neolithic Britain.

However, Professor Gaffney says we will ‘probably not’ ever know exactly why these pits were built.