‘Tipping point’ reached in creation of brain chips to help ‘unlock’ minds of people with paralysis | Science, Climate & Tech News

Decades after the first demonstration of brain computer interfaces, we have reached a “tipping point” in creating the first reliable devices that can read our thoughts, according to the man who pioneered the technology.

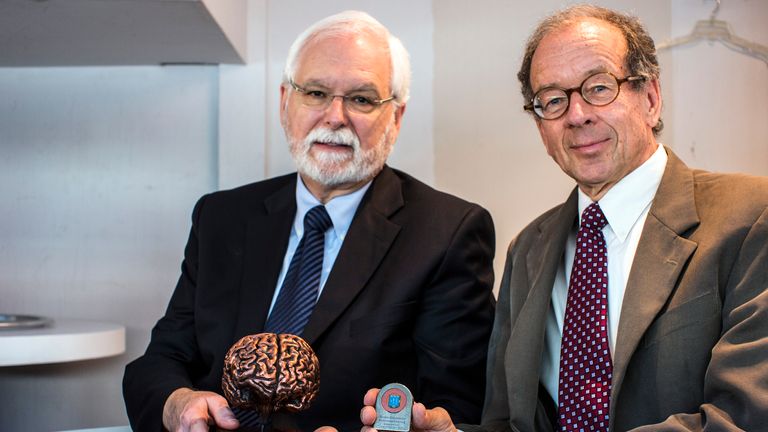

Professor John Donoghue, who developed BrainGate – the first “brain chip” – at Brown University in Rhode Island, has just shared in the Queen Elizabeth Prize, the world’s preeminent engineering award, in recognition of his work to “unlock” the minds of people with paralysis.

“If you want to control a computer, or you want to be able to restore speech, I think there’s no reason why we can’t see those as fast as somebody can produce a device that’s approved,” said the neuroscientist.

Getting devices “approved” is now what it’s all about. That means satisfying medical regulators that the benefits of surgically implanting a chip in the brain outweigh the risks.

And why the first human trials are focusing on those in the greatest medical need, like people paralysed from the neck down.

Elon Musk‘s Neuralink is one of about a dozen companies now working to commercialise BCIs (brain computer interface), or brain chips.

Its technology is based on Prof Donoghue’s early work – an array of electrodes connected to a computer chip that can detect nerve signals in an area of brain tissue, then decode the signals to restore function that has been lost.

Prof Donoghue and his team were the first to show a BCI could be used to restore deliberate movement – “control” they call it – to a paralysed individual.

More than two decades ago, when he embarked on BCI research, some neuroscientists weren’t even sure the brain regions in people with severe paralysis still worked.

Some suspected they might wither through lack of use in the same way the patient’s limbs are prone to do once nerve signals from the brain are lost.

He proved them wrong.

Read more from Sky News:

Instagram and YouTube ‘engineer addiction’

Drinking tea and coffee may reduce dementia risk

“I remember this vividly as we turned it on the very first time,” said Prof Donoghue.

“Is there going to be anything there or are all the neurons just going to be silent? And when we turned it on, it was just busy with activity… at that point, I knew it was going to work.”

Work it did. In a series of experiments, Prof Donoghue’s team showed their BrainGate chip and associated software to decode signals from the motor cortex of a volunteer’s brain could allow them to move a cursor on a screen, turn words into speech and control a robotic arm.

So why, more than a decade since some of those demonstrations, are devices only now going into the first clinical trials?

“You can put an electrode in the brain, first in animals and then people, and it can work, but you need to have a technology that can be safe in the brain and implanted there forever,” explained Prof Donoghue.

Making computer chips and electrodes that minimise the risk of infection, can be implanted in the relevant part of brain tissue without damaging it, and don’t need to be repaired, are major engineering challenges.

And issues that wouldn’t worry an electronics engineer too much are a major problem for biologists.

“If you have a device that’s got a processor of electronics on it, it gets hot, just like your phone gets really hot,” said Prof Donoghue.

“You can’t have that. The brain tolerates just a degree or two.”

But with three companies with BCI devices of different designs in human trials for the first time, Prof Donoghue believes the field is finally taking off.

“The prize is such an important recognition that things are changing all of a sudden,” he said.

Is mind reading in our future?

Well-funded companies like Neuralink are likely to succeed in getting approval for a device to help people with severe paralysis, the professor believes.

However, further inroads into restoring speech, or vision in those who have lost it, and ensuring that the devices remain reliable for the lifetime of a person, are still huge engineering and neuroscience challenges.

Prof Donoghue believes brain chips aren’t currently capable of gathering and processing enough information to be close to “reading” our minds.

But the possibility that an unintended thought, or word, could be picked up by a brain chip means we should be thinking seriously now about the ethical implications of the devices.

“It is a concern,” he said.

“As we learn more and more, we can gain more about what you’re thinking about. I think ethically, we need to think about how we protect the data from an individual.”