Scientists have long speculated what caused the downfall of the Neanderthals, but a new study suggests they never truly went extinct at all.

Scientists in Italy and Switzerland claim the ancient group of archaic humans didn’t experience a ‘true extinction’ because their DNA exists in people today.

Over as little as 10,000 years, our species, Homo sapeins, mated and produced offspring with Neanderthals as part of a gradual ‘genetic assimilation’.

‘Our results highlight genetic admixture as a possible key mechanism driving their disappearance,’ say the experts in a new paper.

‘Neanderthal disappearance rather than a true extinction might be conceived as the result of genetic dilution.’

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthaliensis) were a close human ancestor that lived in Europe and Western Asia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago.

The scientific community already knows Homo sapiens had sex with Neanderthals because DNA from Neanderthals has been found in the genomes of modern humans.

In fact, most non–Africans today inherit one to two per cent of their ancestry from Neanderthals.

Neanderthals, who were already established in Europe and Asia when homo sapiens left Africa, had large noses, strong double–arched brow ridge and relatively short and stocky bodies. Reasons for their demise vary, but experts have suggested they were vulnerable to climate change or lost violent battles with homo sapiens for resources, like food and shelter. Pictured, a Neanderthal man at the human evolution exhibit at the Natural History Museum

Our species, Homo sapiens, existed at the same time as Neanderthals for several thousand years, before we became dominant.

Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa 60,000 to 70,000 years ago to Eurasia (Europe and Asia) – where they found Neanderthals.

When the two species first encountered each other, they likely used basic verbal communication or even languages – possibly enough to understand each other.

What’s more, primitive sexual urges meant the two species couldn’t resist each other, despite the physical differences.

This ancient relative had large noses, strong double–arched brow ridge and relatively short and stocky bodies, skeletal evidence shows.

Whatever the circumstances of the two species copulating, we know they birthed healthy offspring together because they were so genetically alike, which is why humans today have some Neanderthal DNA.

The two species bred with each other for about 7,000 years, until Neanderthals began to die out and disappear, the reason for which ‘remains a subject of intense debate’, according to the study authors.

‘Evidence indicates that Neanderthal extinction was a gradual phenomenon, with the loss of local populations at different times,’ say the team, led by Andrea Amadei at the University of Rome Tor Vergata.

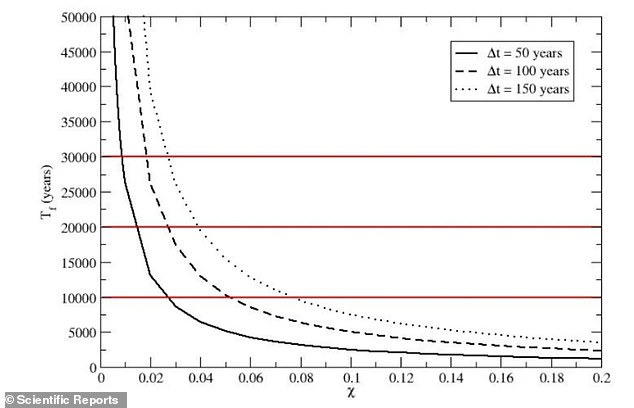

Results suggest that long–term breeding between the two species saw complete ‘genetic absorption’ in as little as 10,000 years or at most 30,000 years

The team used a simple mathematical model to focusing on the impact of small–scale, recurring modern human immigrations into Eurasia.

Results suggest that long–term breeding between the two species saw complete ‘genetic absorption’ in as little as 10,000 years or at most 30,000 years.

The team theorize that there were successive ‘genetic perturbations’ by Homo sapiens into the Neanderthal communities leading to the latter’s ‘genetic dilution’ and downfall.

The smaller size of the Neanderthal population of ‘only a few thousands’ compared with the Homo sapiens population may partly account for the fact we became the dominant species rather than the other way around.

‘Sustained gene flow from a demographically larger species could account for Neanderthals’ genetic absorption into modern humans,’ the team point out.

They acknowledge that other factors may have contributed to the decline of Neanderthals, such as environmental change, but the fact Neanderthal DNA still remains in humans today arguably means that it cannot be considered an extinction in the true sense of the word, at least genetically.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, provides a plausible explanation for the gradual disappearance of Neanderthals – a ‘pivotal moment in human evolution’.

It also provides little support for the idea Neanderthals were wiped out by a sudden ‘catastrophic climatic event’ as some have proposed.

‘Our results highlight genetic admixture as a possible key mechanism driving their disappearance,’ the experts conclude.

‘Genetic admixture can provide another robust explanation for the observed Neanderthal demise, but does not exclude that other factors may have played a substantial role in the disappearance of Neanderthals.

‘Future studies incorporating both genetic and archaeological data will be crucial in refining our understanding of this pivotal moment in human evolution.’

Interactions between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals weren’t all civil, however – possibly another factor accounting for their demise.

Marks on ancient skulls and evidence of weapons suggest Neanderthals and homo sapiens engaged in brutal fights.

Another hypotheses focuses on the competition between Neanderthals and modern humans for space and resources.