A hymn dedicated to the ancient city of Babylon has been discovered after 2,100 years.

Sung to the god Marduk, patron deity of the great city, the poem describes Babylon’s flowing rivers, jewelled gates, and ‘bathed priests’ in stunning detail.

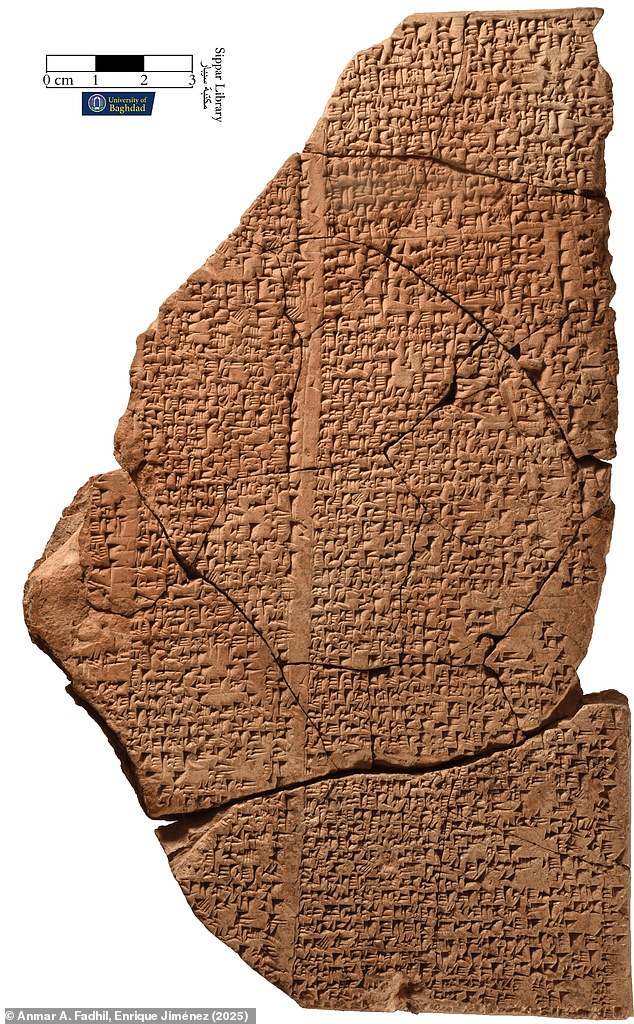

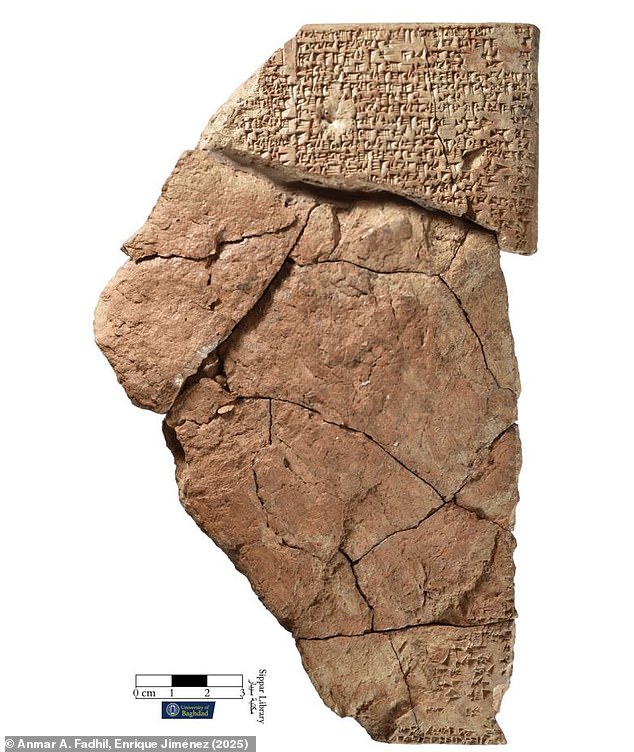

Although the song was lost to time after Alexander the Great captured the city, fragments of clay tablets survived in the ruins of Sippar, a city 40 miles to the North.

In a process that would have taken ‘decades’ to complete by hand, researchers used AI to piece together 30 different tablet pieces and recover the lost hymn.

Originally 250 lines long, scientists have been able to translate a third of the original cuneiform text.

These lines reveal a uniquely rich and detailed description of aspects of Babylonian life that had never been recorded before.

Lead researcher Professor Enrique Jiménez, of Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU), told MailOnline that the hymn’s literary quality is ‘exceptional’.

‘It’s meticulously structured, with each section flowing seamlessly into the next,’ he said.

Scientists have used AI to combine 30 fragments of clay tablets to reconstruct an ancient Babylonian hymn, 2,100 years after it was lost

The hymn was sung in praise the city of Babylon (artist’s impression)a. Founded in 6000 BC, Babylon was once the largest city in the world

The hymn begins with grand praise to the god Marduk, calling him the ‘architect of the universe’.

The poem’s author then turns to the city of Babylon, describing it as a rich paradise of abundance.

The hymn writes: ‘Like the sea, (Babylon) proffers her yield, like a garden of fruit, she flourishes in her charms, like a wave, her swell brings her bounties rolling in.’

There are also descriptions of the river Euphrates, which still runs through modern-day Iraq, and its floodplains upon which ‘herds and flocks lie on verdant pastures’.

However, as Professor Jiménez points out, the hymn also gives a unique insight into Babylonian morality.

Professor Jiménez: ‘The hymn reflects ideals the Babylonians valued, such as respect for foreigners and protection of the vulnerable.’

The hymn praises priests who do not ‘humiliate’ foreigners, free prisoners, and offer ‘succor and favor’ to orphans.

Likewise, the poem gives some striking details about the lives of women in Babylon who are rarely mentioned elsewhere.

Only fragments of the poem survive, many copied out by children in school up to 1,400 years after the hymn was first composed

The hymn praises Babylon’s jewelled gates, flowing rivers, verdant pastures, and ‘bathed priests’ in stunning detail. Pictured: A recreation of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin

‘For example, it reveals that one group of priestesses acted as midwives—a role unattested in other sources,’ says Professor Jiménez.

The poem describes these priestesses as ‘cloistered women who, with their skill, nourish the womb with life’.

What makes this discovery particularly exciting is how important the poem appears to have been to the Babylonians.

Babylonians recorded information in a writing system called cuneiform, which involved pressing a sharpened reed into soft clay to make triangular marks.

Even after Babylon was conquered in 331 BC, many of these clay tablets have survived until the present day.

Excavations at the city of Sippar have yielded hundreds of clay tablets which, according to legends, were placed there by Noah to hide them from the floodwaters.

These fragments show that the hymn was being used in Babylonian schools as an educational tool for around 1,000 years.

Professor Jiménez believes that the poem was originally written sometime around 1500-1300, making it one of the earliest long poems from Babylon.

After Babylon was captured in 331 BC by Alexander the Great, the poem was lost to time. Its rediscovery gives a unique insight into the lives and attitudes of Babylonians. Pictured: the Ninmakh Temple or Babylon, built in 562 BC

The researchers say that the Hymn to Babylon would have circulated at the same time as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest long poem in recorded history (pictured)

The oldest surviving version of the text comes from a fragment belonging to a school dating to the seventh century BC.

However, the tablets from Sippar show that the poem was still being copied out by children in schools right up to the last days of Babylon in 100 BC – 1,400 years after it was composed.

That is the equivalent of children today learning about a poem written around 700 AD, such as the Old English poem Beowulf.

The researchers say that this importance would have put the Hymn to Babylon alongside the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known long-form poem in human history.

Professor Jiménez says that, although the hymn was written later than the Epic of Gilgamesh, both would have ‘circulated side by side for centuries’.

Unlike the Epic of Gilgamesh, the researchers believe that the Hymn to Babylon was written by a single author rather than by collecting traditional texts over time.

Although this author’s name is currently unknown, Professor Jiménez remains hopeful that this may change in the future.

He says: ‘We have been digitising the British Museum’s cuneiform collection over the last few years and discovered previously unknown author names, so we may yet identify the hymn’s creator in the future.’