Britain is seeing a ‘remarkable’ surge in numbers of frilly–mouthed jellyfish, the largest jellyfish known to these shores.

There were 310 sightings of the species around Britain and Ireland in the last 12 months – a whopping yearly increase of 230 per cent, experts at the Marine Conservation Society reveal.

Also known as the barrel jellyfish, this ‘relatively gentle giant’ has a huge mushroom shaped ‘bell’ and a bunch of eight frilly tentacles below.

Growing to the size of a dustbin lid, the frilly–mouthed jellyfish is often found washed up on beaches in May and June, mostly in Scotland and Wales.

The sting of the barrel jellyfish is not normally harmful to humans, though if you find one on the beach it’s best not to handle it as they can still sting when dead.

Experts are unsure what’s behind the massive surge in numbers, but it may be linked to warmer sea temperatures and changing ocean currents.

Jellyfish play a crucial role in the ocean, helping to move carbon through marine food webs, supporting biodiversity and acting as natural indicators of changing ocean conditions.

They are also edible and may provide a more sustainable alternative to certain fish in the years to come.

The frilly–mouthed jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo), also known as the barrel jellyfish, is the UK’s largest jellyfish, growing to the size of a dustbin lid

This large translucent jellyfish has a huge mushroom shaped bell and a bunch of eight frilly tentacles below. They are often found washed up on beaches in May and June

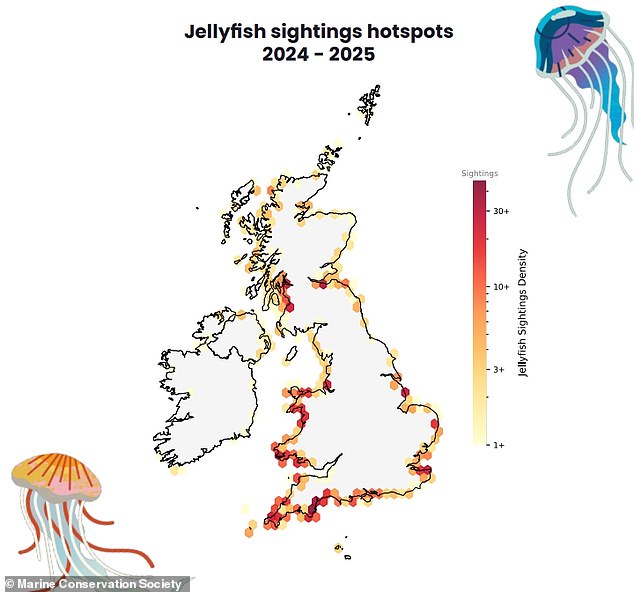

The Marine Conservation Society’s annual Wildlife Sightings Report of jellyfish and other types of aquatic invertebrate known as ‘cnidarian’ relies on reported sightings from members of the public.

According to the report, 1,327 were sighted across the UK and Ireland in the period October 1, 2024 to September 30, 2025.

Of this figure, 310 (23.3 per cent) were the frilly–mouthed jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo), which is slightly less than the moon jellyfish, the most spotted species for the second year in a row.

In all, 316 moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) were sighted in the 12–month period, mostly in July, making up 23.8 per cent of all reports.

About a foot in diameter, the dome–shaped moon jellyfish is almost entirely translucent apart from four purple circular markings around the centre.

It often washes up on UK beaches, although there’s no need to worry about this species because it doesn’t sting humans, according to Wildlife Trusts.

Third on the list is the compass jellyfish (Chrysaora hysoscella), named for its arrangement of brown lines on its whiteish–yellow, umbrella–like body.

‘They may look beautiful – but they give a nasty sting so keep your distance,’ Wildlife Trusts says about this species.

Jellyfish are present throughout UK seas, with large blooms of most species appearing in the spring and lasting through to autumn

The moon jellyfish (pictured) is the most common jellyfish in British waters. This jellyfish is almost entirely translucent apart from four purple circular markings around the centre. It is not dangerous to humans

Beware of the compass jellyfish (Chrysaora hysoscella), which is a translucent yellowish–white jellyfish with detailed brown markings around the fringe and on the top of the ‘bell’

Other species on the list include lion’s mane jellyfish, the blue jellyfish and the highly dangerous Portuguese man o’ war, which is a species of siphonophore, a group of animals that are closely related to jellyfish.

The Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) certainly has an incredible appearance, with a bulbous bladder–shaped body and iridescent colouring.

But its long, dangling, blueish–violet tentacles deliver a painful sting that can cause red welts, blisters, and in severe cases, fever, shock, or even complications affecting the heart and lungs.

While deaths are rare, allergic reactions or cardiovascular issues caused by the venom can sometimes be fatal.

Even after the Portuguese man o’ war has died, its tentacles remain capable of stinging, meaning that detached or dead specimens washed ashore are just as dangerous as live ones.

Some may be pleased to hear therefore that sightings of the Portuguese man o’ war plummeted by over 80 per cent, dropping from second place a year ago to eighth place in 2025.

Portuguese man o’ war sightings made up less than four per cent of total sightings in the category this year, with the majority spotted in England.

Another cnidarian on the list is known as the by–the–wind–sailor (Velella velella), which only made up 0.5 per cent of the sightings.

Even after the Portuguese man o’ war has died, its tentacles remain capable of stinging, meaning that detached or dead specimens washed ashore are just as dangerous as live ones

The report also gives an insight into one of the primary predators of jellyfish in British waters – the sea turtle.

It reveals there were 12 confirmed reports of turtles around British waters in the last year – an increase of three compared to last year.

Nine of these were leatherback sea turtles, eight of which were alive. The leatherback sea turtle is the largest turtle in the world and the most frequently recorded turtle in UK waters. In the last year it was mostly seen off the southwest coast.

Of the remaining three, one live loggerhead turtle was seen in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland and two turtles were ‘unidentified’.

Overall, turtle sightings this year were ‘encouraging’ but remained rare, as they are still considered vulnerable with many populations at risk of extinction.

Most sightings occurred during the summer months, when leatherbacks migrate to British waters to feed on jellyfish.