In a promising update, scientists have revealed that the ozone hole is healing – and it could soon close up for good.

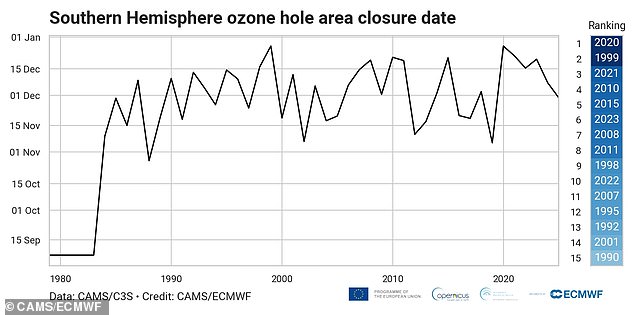

The Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS) found that the hole – which appears yearly over Antarctica – closed on Monday (December 1).

This is not only earlier than expected, but also marks the earliest closure since 2019.

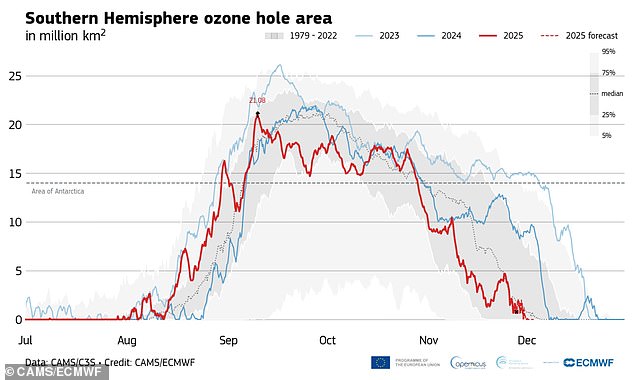

What’s more, the 2025 ozone hole at its maximum extent was the smallest in five years, at 8.13 million sq miles (21.08 million km2).

It marks the second consecutive year of relatively small holes compared to the series of large and long-lasting ozone holes from 2020-2023.

And it fuels hopes for the ozone layer’s complete recovery – potentially within the next couple of decades.

Dr Laurence Rouil, director of the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), called the earlier closure and relatively small size ‘a reassuring sign’.

‘It reflects the steady year-on-year progress we are now observing in the recovery of the ozone layer,’ he said.

Scientists confirm the 2025 ozone hole at its maximum extent was the smallest in five years, at 8.13 million sq miles (21.08 million km2)

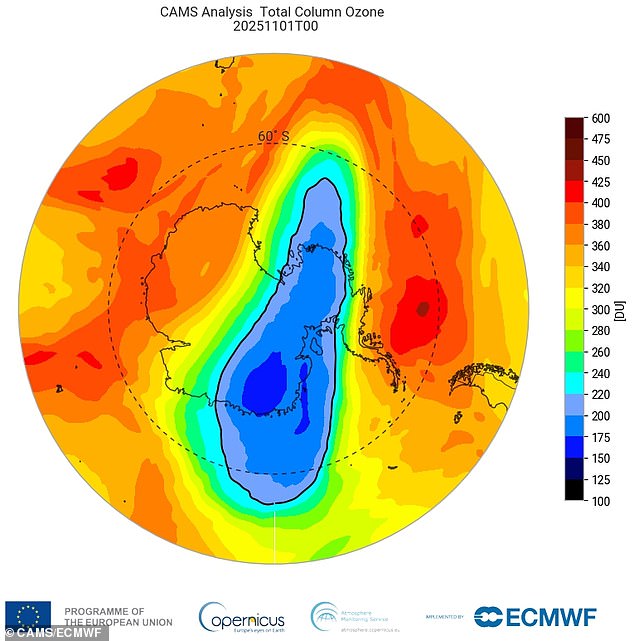

The ozone hole is not technically a ‘hole’ where no ozone is present, but is actually a region of exceptionally depleted ozone over the Antarctic.

Generally, it opens every August, reaches its maximum size in September or October and closes in late November or early December.

In 2025, the ozone hole developed relatively early through mid-August, following a similar trajectory to the large ozone hole of 2023.

Towards the end of August 2025, its size reduced slightly before growing to a maximum area of 8.13 million sq miles/21.08 million km2 in early September.

This size is ‘fairly typical’ at this point but well below the maximum of 10.07 million sq miles/26.1 million km2 observed in 2023.

During September, the size of the ozone hole started to gradually reduce but ‘remained at a considerable size’, experts found.

Through September and October, it was between 5.7 million sq miles/15 million km2 (roughly the area of Antarctica) and 7.7 million sq miles/20 million km2.

But the area of the ozone hole declined quickly during the first half of November, indicating the possibility of an early closure.

The ozone hole is not technically a ‘hole’ where no ozone is present, but is actually a region of exceptionally depleted ozone in the stratosphere over the Antarctic. Pictured, November 1, 2025

The Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) confirms that the 2025 Antarctic ozone hole came to an end December 1, marking the earliest closure since 2019

A persistent small area of low ozone persisted through the second half of the month, until it fully closed on December 1.

It marks the the earliest closure since 2019 (November 12) and one of the earliest closures of the ozone hole in the past four decades.

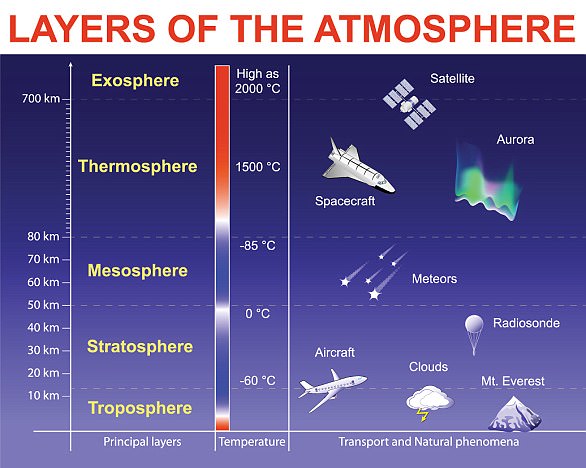

Located in the stratosphere (the second layer of Earth’s atmosphere), the ozone layer absorbs almost all of the sun’s harmful incoming ultraviolet radiation (UVB) – making it fundamental to protecting life on Earth’s surface

Without the ozone layer, there would be severe increases of solar UV radiation, which would damage our DNA and make skin cancer more common.

Having a hole in the ozone layer therefore increases the amount of UV that reaches Earth’s surface – and the bigger the hole is, the more we’re exposed.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that the ozone hole was first discovered, by British meteorologist Jonathan Shanklin, making global headlines.

As scientists explained, the hole was created by the release of human-made chemicals, particularly CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons), into the atmosphere.

It led to the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to halt the production of CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances (ODS), signed in December 1987.

While the Montreal Agreement phased out 99 per cent of all ozone-depleting chemicals, the remaining one per cent still lingers in Earth’s upper atmosphere.

During the southern hemisphere’s winter, a large pillar of extremely cold, rotating air forms above the Antarctic.

Maximum yearly extent of the ozone hole: The 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 ozone holes were particularly large and long lasting

This concentrates the remaining CFCs in an area where cold conditions and solar radiation enable them to deplete the layer of ozone gas.

Experts hope CFCs will eventually be eliminated from the atmosphere, although this process is slow due to their chemical stability.

It is estimated that the ban will enable a recovery of the ozone layer by 2050 and 2066, according to experts at CAMS.

‘This progress should be celebrated as a timely reminder of what can be achieved when the international community works together to address global environmental challenges,’ said Dr Rouil.

Meanwhile, a UN report said the ozone hole could heal over by 2040.